Tuesday, August 28, 2018

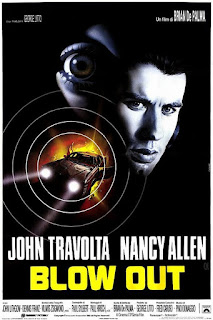

Short Take: Blow Out

The turmoil of the 1960s and early 1970s, from the assassination of John F. Kennedy to the Watergate scandal, gave rise to the golden age of the political-conspiracy thriller. Blow Out, written and directed by Brian De Palma, is one of the best. While recording material for a horror-movie project, a sound-effects specialist (John Travolta) witnesses what appears to be an automobile accident. The driver, an expected presidential candidate, is killed, but the sound man manages to save a young woman (Nancy Allen) who was also in the vehicle. Later, after reviewing his tapes, he believes the car's tire was shot out, and the politician was murdered. His determination to prove an assassination happened takes over his life. It turns out the incident had also been filmed, and the need to locate the cameraman (Dennis Franz) becomes paramount. The sound man enlists the help of the woman, but he doesn't realize all of them have been targeted by an operative (John Lithgow) working for the politician's rivals. The story is terrifically suspenseful, and Brian De Palma's genius for interrogating and expanding on existing film tropes has never been on better display. The sound man's efforts to recreate the murder through sound and image recall the photographer in the Michelangelo Antonioni film Blow-Up. But De Palma's aims are different than Antonioni's. He isn't engaging in social commentary. Much of the story is structured around the recreation process, and here it is much more extensive and varied. The sound man's theory of the events is validated, although the viewer is made fully aware of the artifice necessary to get there. One recognizes (and the film obliquely acknowledges) the skepticism the recreation effort would meet. De Palma also includes things all his own, such as the hallucinatory scene in which the sound man discovers his tape library has been erased. And then there's the film's most powerful element: De Palma's exploration of a trope of movie violence and the viewer's desensitization to it. The trope is treated as a running gag for much of the film. In the story's climax, it is used in conventional dramatic terms. The epilogue, though, turns the trope against the viewer. The final scene isn't the least bit violent on the surface, but it's chillingly horrific, and a brilliantly poetic transformation of meaning. De Palma seems to be saying, "This trope here? It can be funny. It can be dramatic. But it's also about pain, and terror, and death. Don't ever forget that." He ensures no one ever will. It's a great, provocative ending. The velvety cinematography is by Vilmos Zsigmond, with a parade set piece shot by László Kovács after the Zsigmond footage was lost. Paul Hirsch provided the virtuoso editing. Pino Donaggio contributed the fine score.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment