Thursday, August 30, 2018

Short Take: Lost in America

With Lost in America, director, star, and co-writer Albert Brooks delivers a cutting, hilarious satire of the baby-boomer bourgeois mindset. Its targets range from 1960s nostalgia to careerist entitlement to yuppie consumerism. Brooks plays a thirtysomething Los Angeles advertising executive who, after getting a different promotion than he expected, throws a tantrum that gets him fired. He convinces his wife (Julie Hagerty) to quit her job, and seeing himself as kin to the outlaw counterculture bikers in the film Easy Rider, resolves to “drop out.” The couple sell their home, and decide to spend their lives seeing the “real America” while living off the land--in a 30-foot luxury recreational vehicle, with a six-figure cash “nest egg” for expenses. They of course lose the money, and find themselves in another “real America”: the one of trailer parks, employment agencies, and minimum-wage jobs. Brooks is a terrific comic actor. The protagonist is an entitled, obsessive-compulsive fussbudget, and Brooks inhabits the fellow so completely one might think he was living the part. The character’s frequent rants are small masterpieces of timing and delivery--both brilliantly orchestrated and dizzyingly funny. The script, co-written with Monica Johnson, gives the protagonist other comic opportunities, such as his hilarious dialogues with a casino pit boss (Garry Marshall) and an employment-agency job counselor (Art Frankel). But the picture’s most incisive bit is visual: the sight of these two upscale "drop-outs" tooling around the majestic landscapes of the American Southwest in their high-end Winnebago. It’s a terrific symbol of how absurdly pretentious bourgeois self-deception can get. This is a great American comedy. The cinematography is by Eric Saarinen.

Wednesday, August 29, 2018

Short Take: E. T. the Extra-Terrestrial

Director Steven Spielberg's E. T. the Extra-Terrestrial is an enchanting picture, and one of the two or three finest children's movies ever made. The story is about an extra-terrestrial visitor who is accidentally left behind by its landing party. Looking for shelter, it befriends a lonely 10-year-old (Henry Thomas), who lives in a suburban development with his mother (Dee Wallace), older brother (Robert Macnaughton), and kid sister (Drew Barrymore). The drama comes from the alien's efforts to contact its people, and to stay out of the clutches of the government investigators looking to capture it. Spielberg sets up the story with a deft mix of slapstick, visual poetry, and emotional nuance. He also delivers some magical moments, such as the airborne bicycle ride over the forest near the 10-year-old's home. The heart of the story, though, is the rapport between the alien and the 10-year-old. In dramatizing it, Spielberg hits some of the most powerful notes of love and friendship in all of film. This sentimental adventure movie leaves one thrilled, happy, and teary-eyed, all at the same time. The screenplay is credited to Melissa Mathison. Allen Daviau provided the cinematography. The score is by John Williams. The wizardly Carlo Rambaldi designed the alien and oversaw the animatronics.

Tuesday, August 28, 2018

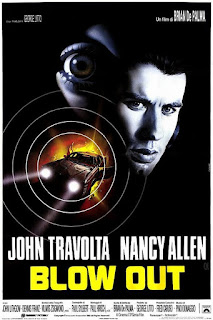

Short Take: Blow Out

The turmoil of the 1960s and early 1970s, from the assassination of John F. Kennedy to the Watergate scandal, gave rise to the golden age of the political-conspiracy thriller. Blow Out, written and directed by Brian De Palma, is one of the best. While recording material for a horror-movie project, a sound-effects specialist (John Travolta) witnesses what appears to be an automobile accident. The driver, an expected presidential candidate, is killed, but the sound man manages to save a young woman (Nancy Allen) who was also in the vehicle. Later, after reviewing his tapes, he believes the car's tire was shot out, and the politician was murdered. His determination to prove an assassination happened takes over his life. It turns out the incident had also been filmed, and the need to locate the cameraman (Dennis Franz) becomes paramount. The sound man enlists the help of the woman, but he doesn't realize all of them have been targeted by an operative (John Lithgow) working for the politician's rivals. The story is terrifically suspenseful, and Brian De Palma's genius for interrogating and expanding on existing film tropes has never been on better display. The sound man's efforts to recreate the murder through sound and image recall the photographer in the Michelangelo Antonioni film Blow-Up. But De Palma's aims are different than Antonioni's. He isn't engaging in social commentary. Much of the story is structured around the recreation process, and here it is much more extensive and varied. The sound man's theory of the events is validated, although the viewer is made fully aware of the artifice necessary to get there. One recognizes (and the film obliquely acknowledges) the skepticism the recreation effort would meet. De Palma also includes things all his own, such as the hallucinatory scene in which the sound man discovers his tape library has been erased. And then there's the film's most powerful element: De Palma's exploration of a trope of movie violence and the viewer's desensitization to it. The trope is treated as a running gag for much of the film. In the story's climax, it is used in conventional dramatic terms. The epilogue, though, turns the trope against the viewer. The final scene isn't the least bit violent on the surface, but it's chillingly horrific, and a brilliantly poetic transformation of meaning. De Palma seems to be saying, "This trope here? It can be funny. It can be dramatic. But it's also about pain, and terror, and death. Don't ever forget that." He ensures no one ever will. It's a great, provocative ending. The velvety cinematography is by Vilmos Zsigmond, with a parade set piece shot by László Kovács after the Zsigmond footage was lost. Paul Hirsch provided the virtuoso editing. Pino Donaggio contributed the fine score.

Sunday, August 26, 2018

Short Take: Koyaanisqatsi

Koyaanisqatsi, a documentary directed by Godfrey Reggio, is a sublime film. One is tempted to describe it as a non-narrative effort, but that’s not quite accurate. The imagery has a fairly obvious theme: the beauty of the land is despoiled by the presence of humanity and its technology. But the simple (if not callow) environmental polemic is fairly easy to overlook. Reggio uses basic juxtaposition to convey the theme. It's hardly sophisticated, but he thankfully doesn't belabor the effect. What is sophisticated is his ability to shape the waves of environmental imagery into an elegant compositional whole. The shots are never static; with immobile subjects such as landscape formations and urban buildings, the camera moves for them. When there’s movement within the frame, Reggio often varies the speed with time-lapse and slow-motion techniques. The imagery never lacks for grandeur, and the visual rhythms always keep one attentive. With the counterpoint of composer Philip Glass’ gorgeous score, the film makes for a powerful immersive experience. It’s a cinematic symphony. Ron Fricke provided the breathtaking cinematography. Fricke and Alton Walpole are credited with the editing. The film is the first of a trilogy; Powaqqatsi and Naqoyqatsi followed.

Short Take: All That Jazz

One may be inclined to think of All That Jazz, directed and co-written by Bob Fosse, as two movies: Jazz and All That. The Jazz movie is an enormously entertaining backstage drama. It’s a fictional treatment of Fosse’s experiences during the post-production of his 1974 film Lenny, and the concurrent casting and rehearsals of the stage musical Chicago, which debuted on Broadway in 1975. The director-choreographer’s self-portrait is warts-and-all. The Fosse character (played by Roy Scheider) is a womanizer and an obsessive workaholic. He’s shown throwing his all into his two projects while trying not to alienate his producers, the young dancer he’s grooming (Deborah Geffner), and those in his personal life: his steady girlfriend (Ann Reinking), his ex-wife and stage-show leading lady (Leland Palmer), and his 12-year-old daughter (Erzsébet Foldi). One sees all the angst of the director’s life, but one also sees the work he takes pride in. There are the occasional joys as well, such as the happier moments with his daughter and girlfriend. The portrayal is anchored by Roy Scheider’s outstanding performance. He’s completely convincing as a harried, occasionally tyrannical perfectionist, and he makes it all of a piece with the character’s considerable charm. Scheider makes one believe one is watching Fosse as he truly is. That’s the Jazz movie, and it's terrific. However, there is also the All That movie mixed in. Following the obvious lead of the Federico Fellini film 8½, Fosse includes multiple fantasy scenes in which the director reflects on his life. These climax in a tasteless five-song production-number finale that may be the most insufferable musical sequence ever put on film. Thankfully, the non-fantasy material is so strong that one quickly puts the All That movie out of mind. The Jazz movie reigns. Giuseppe Rotunno provided the cinematography, and Alan Heim is credited with the top-notch editing. Robert Alan Aurthur is credited with co-writing the script.

Saturday, August 25, 2018

Short Take: Ran

The arts have their ironies. The two best film versions of the plays of William Shakespeare, the English language’s greatest writer, are not in English. Ran and Throne of Blood, which adapt, respectively, King Lear and Macbeth, are both Japanese-language productions. The films don't try to transpose the richness of Shakespeare’s language, considered by many to be the plays’ greatest glory. Their director, Akira Kurosawa, compensated with powerful imagery that eloquently dramatizes the plays’ meanings. Kurosawa made the material his own, and the films’ visionary quality is what sets them apart from other screen treatments. A further irony: Ran, arguably the more impressive of the two pictures, takes the most liberty with its source material. Set in 16th-century Japan, it’s no longer the story of Lear and his three daughters. It’s now the tale of Lord Hidetora (Tatsuya Nakadai) and his three sons (Akira Terao, Jinpachi Nezu, and Daisuke Ryu). Edmund the Bastard, who seduced two of Lear’s daughters in his quest for power, is reimagined as the Lady Kaede (Mieko Harada), the wife of Hidetora’s eldest son. A monstrously vengeful woman, she combines Edmund with aspects of Lady Macbeth, Queen Herodias, crime-fiction femmes fatales, and in one startling moment, Count Dracula. The basic plot is the same, though, and none of the principals are winners in the end. The play’s horror is rooted in the destruction of family bonds, both between parents and children, and siblings with one another. Kurosawa remains true to this, and he most powerfully conveys it in one awesomely apocalyptic set piece. Hidetora, who has been cast out by the two elder sons, takes refuge with his entourage in the fortress vacated by the third. The elder sons lay siege to the fortress with the troops Hidetora had placed under their command, and the screen drips blood from the massacre. Hidetora sits in stunned silence as the flaming arrows shot by the sons’ archers fly all around him. One of the sons is killed, and Hidetora, driven mad by despair, staggers out of the fortress. The sons’ troops clear the way as he passes, showing the deference for their former leader that the sons likely never felt. It’s as great an epic scene as one will ever find in movies. The rest of the film is almost as impressive, and the visuals are never less than remarkable. Kurosawa often evokes a God’s-eye view of the action, with the characters, in their colorful outfitting, elegantly framed against the backdrop of the sets and the spectacular landscapes. The cinematography is by Takao Saito, Masaharu Ueda, and Asakuze Nakai, with production design by Shinobu Muraki and Yoshiro Muraki. Emi Wada designed the gorgeous costumes. (The outfits, all created by hand, reportedly took nearly three years to complete.) The harshly beautiful music, heavy with discord and percussion, is by Toru Takemitsu. Kurosawa collaborated on the script with Hideo Oguni and Masato Ide.

Friday, August 24, 2018

Short Take: General Hospital (1978-1987)

In 1978, Gloria Monty, a veteran director of daytime-TV soap operas, was hired to be executive producer and head showrunner of General Hospital, an ABC-network soap that was on the verge of cancellation. Over the next three years, she transformed the series into a pop-culture phenomenon and the most popular daytime soap to ever air on TV. Monty moved the show's emphasis from domestic and medical melodrama to the excitement of fanciful adventure serials, pulp-crime stories, and romance among the young and glamorous. The character ensemble she established couldn't have been more compelling. Among the more notable regulars: Luke Spencer (Anthony Geary), a straddling-both-sides-of-the-law antihero adventurer; Laura Webber (Genie Francis), Luke's major love interest; Robert Scorpio (Tristan Rogers), an Australian-born espionage and law-enforcement operative; Heather Webber (Robin Mattson), a devious, disturbed young woman who was key to the show's most compelling murder mystery; Scotty Baldwin (Kin Shriner), a sleazy young attorney who was Luke's frequent nemesis; Holly Sutton (Emma Samms), a high-stakes grifter from England; Anna Devane (Finola Hughes), a one-time confederate and lover of Scorpio's who wanted to hang the gun up for good, but never did; Frisco Jones (Jack Wagner), a handsome musician turned police officer; and Felicia Cummings (Kristina Malandro), Frisco's love interest, whose beauty was only surpassed by her talent for finding danger. The series was a pastiche of probably every pulp-suspense and romantic-melodrama plot out there. (The Ice Princess storyline, the program's most famous, while best known for the Luke and Laura romance, began as a play on The Maltese Falcon and ended as a James Bond-style adventure.) The show was irresistible, and until Monty departed in January 1987, the weekday 3PM hour was must-watch TV. Looking back, the only disappointment is that one had to be there to appreciate it. The hundreds if not thousands of hours of episodes encompassing Gloria Monty's tenure have not been collected on video, and given the volume of material, they probably never will be. Only scattershot YouTube compilations remain.

Thursday, August 23, 2018

Short Take: Robin Williams: A Night at the Met

Robin Williams was perhaps the greatest stand-up comic ever. His material might seem modest on paper, but he transformed it with his manic energy, his knack for impressions, and most of all, his brilliant free-associative digressions and embellishments. One laughs, but one also watches in awe at his mind working. Robin Williams: A Night at the Met, which edits together a pair of performances at New York's Metropolitan Opera House, is a marvelous showcase for his genius. He glides from extended takes on alcoholism and drug addiction to ones on sex and fatherhood, with tangents on international affairs and domestic politics. On the first viewing, one never knows what it is coming. Williams has one laughing every moment. On subsequent viewings, his delivery keeps everything fresh. The film originally aired on Home Box Office. It has been marketed under various titles, including Robin Williams: An Evening at the Met and Robin Williams Live!. An audio-only version won the 1988 Grammy for Best Comedy Recording. The credited director is Bruce Gowers.

Short Take: Round Midnight

The American jazz prevalent in the 1950s and 1960s—bebop, modal, and hard bop, among other styles—is considered by many to be the finest music the United States has ever produced. No film has ever done it as much justice as director Bertrand Tavernier’s Round Midnight. The picture, set in 1959, is about the final months of a legendary saxophone player named Dale Turner (played by the real-life saxophone master Dexter Gordon). It’s centered on Dale’s friendship with a French jazz fan (François Cluzet), and the fan’s efforts to keep him sober and focused on his music. The story isn’t of much interest beyond Gordon’s sweet, melancholy performance as Dale. The film’s real glories are the plentiful musical numbers, performed live by Gordon and other first-tier jazz musicians, including pianist Herbie Hancock, saxophonist Wayne Shorter, and guitarist John McLaughlin, among many others. The selections include standards by Cole Porter, Johnny Green, and Vernon Duke, as well as original compositions from Hancock and Gordon. Two special treats are the saxophone-and-vocals duet by Gordon and Lonette McKee on the Gershwins' “How Long Has This Been Going On?,” and Sandra Reeves-Phillips’ raucous party-scene rendition of Bessie Smith's “Put It Right Here.” Tavernier holds the camera on the musicians for long stretches, and one can see the drama of their performances in their faces. In the moments when the camera glides away, it’s invariably to emphasize the atmosphere inside the nightclubs. Tavernier understands live performance is an interaction between players and the audience. It’s wonderful to see performed jazz presented with such love, respect, and filmmaking intelligence. The magnificent cinematography is by Bruno De Keyzer. Herbie Hancock composed the film’s non-diegetic music and oversaw the recording of the performances. The script, by David Rayfiel and Tavernier (with uncredited contributions from Dexter Gordon), is a loose, fictionalized adaptation of Dance of the Infidels, Francis Paudras’ memoir of his friendship with pianist Bud Powell.

Wednesday, August 22, 2018

Short Take: RoboCop (1987)

Director Paul Verhoeven's dystopian action thriller RoboCop is a terrific adventure movie. It may also be the definitive satirical treatment of the 1980s on film. The setting is a near-future Detroit that's a right-wing nightmare of urban lawlessness, albeit without the racism. After a police officer (Peter Weller) is murdered by a crime boss (Kurtwood Smith) and his gang, the officer's remains are appropriated for an experimental cybernetics program. He is resurrected as RoboCop, the first in a proposed line of armored cyborg policemen. His memory was supposed to be erased, but it comes back to him in bits and pieces. He eventually remembers enough to pursue the gang members who ended his previous life. That runs him afoul of a corporate conspiracy to exacerbate crime levels for profit. At every turn, the film pillories corporate greed, keeping-up-with-the-Jones consumerism, and the cultural need to commodify everything. Verhoeven's gleefully transgressive tone makes the satire both vivid and hilarious. Even the film's violence, which would seem shockingly depraved in most contexts, is in keeping with the overall vision. Verhoeven keeps the picture thrillingly paced, and he's also put together a fine cast. Peter Weller is quite affecting as the police officer who becomes RoboCop. The character's eyes, once the armor's helmet is removed, eloquently carry the misery of not knowing the life he has lost. His voice, despite its monotone, carries the ache. Ronny Cox, Miguel Ferrer, and Dan O'Herlihy are sleazy perfection as the slick, sociopathic executives whose company both creates RoboCop and proves his ultimate antagonist. Best of all is Kurtwood Smith as the crime boss. Cackling homicidal maniacs have been a mainstay of crime-centered adventure stories since at least the 1940s, when the Batman comic books introduced the Joker. Several fine actors, including Richard Widmark, Frank Gorshin, and Heath Ledger, have done their most celebrated work in these roles. Smith's performance balances the sniggering viciousness with an air of ruthless determination, and he tops every one of them. The screenplay is credited to Edward Neumeier and Michael Miner. Jost Vacano provided the cinematography, and Frank J. Urioste delivered the top-notch editing. The picture was followed by two vastly inferior sequels and an insipid 2014 remake.

Tuesday, August 21, 2018

Short Take: Dangerous Liaisons

Over the last few decades, no literary work has attracted more interest from filmmakers than Choderlos de Laclos' 1782 novel Les Liaisons dangereuses. Between 1988 and 2018, at least ten adaptations have been produced for film and television worldwide. It's hard to imagine any being better than 1988's Dangerous Liaisons, cracklingly directed by Stephen Frears from a first-rate script by Christopher Hampton. The story, set in pre-Revolution France, centers on two aristocrats: the Marquise de Merteuil (Glenn Close) and the Vicomte de Valmont (John Malkovich). Once lovers, the two are now confidants and occasional partners in romantic gamesmanship. The film begins with the Marquise plotting revenge against a man who has recently broken up with her. She wants Valmont to seduce the virginity-fixated fellow's teenage bride-to-be (Uma Thurman). The Marquise is amused by Valmont's interest in the Madame de Tourvel (Michelle Pfeiffer), the religiously devout wife of a government official, and she agrees to a reward: a night of her favors if he manages both conquests. This sets the stage for the first part of the story, which Frears and Hampton make perhaps the most audaciously hilarious bedroom farce in the history of film. Even more impressive is their powerful handling of the second part. Death and disgrace take over, farce becomes tragedy, and love laughs last. The two aristocrats, smug in their belief they are above love's sentiments, prove themselves love's greatest fools. Frears and Hampton's achievement with the adaptation is two-fold. The first is their realization of the comic possibilities in Laclos' material. (The novel, which tells the story in a series of letters, is an eyebrow-raiser, but it isn't particularly funny.) The second is the deft rendering of the more sympathetic dimensions of the characters, which makes the transition from farce to tragedy possible. Frears and Hampton are helped in this by a knockout cast. In the first part, Glenn Close and John Malkovich play their roles with an arch, flamboyant theatricality: she's all duplicitous smiles and fake sympathy, and he's the quick-witted snake in the ancien régime garden. They completely convey how much the characters enjoy their deviousness. But Close and Malkovich shift very effectively to naturalism when honest emotion breaks through their characters' façades: the Marquise's face melting into lonely desolation when she hears another describe being in love, or Valmont's empathetic retreat from his seduction of Tourvel when he sees the pain in her conflict between desire and faith. There's not a hint of discord between the first part and the second, when the aristocrats' façades and honest feelings are at war. But the performer who does the most to bring the two parts of the story together is Michelle Pfeiffer. She's both vivid and unaffected as Tourvel, and she leaves no doubt the woman is completely without guile. There's no façade in play with Tourvel's initial recoil from Valmont's advances, or her smoldering expression when the two are in bed, or the sweet happiness in her impatience when a servant leads her to meet him. When she goes from being mark to victim, there's no question how completely she's destroyed, or how hideous the aristocrats' games are. Tourvel abandoned her faith for love, and she's left with neither. Pfeiffer and her no-frills directness make a viewer feel it all. The cast also includes Swoosie Kurtz, Keanu Reeves, and Mildred Natwick. The fine cinematography, equally at home in bright sunshine and candlelit rooms, is by Philippe Rousselot. James Acheson provided the gorgeous period costumes. The film was shot at various châteaux outside Paris.

Monday, August 20, 2018

Short Take: Casualties of War

Like many filmmakers of his generation, Brian De Palma regards the literate, visually splendid historical dramas of David Lean as an artistic pinnacle. Casualties of War, his one effort in this mode, is an extraordinary film. It matches Lean’s visual grandeur and thematic intelligence, and outdoes him in terms of dramatic intensity. The script, by David Rabe, is based on the Vietnam War’s Hill 192 incident, which occurred in 1966. A squad of U. S. soldiers kidnapped a South Vietnamese woman while on a reconnaissance mission. Four of the five men took turns raping her, and near the end of the mission, she was murdered. The soldier who refused to participate (played by Michael J. Fox) sought to report the crime, but his efforts were frustrated by his commanding officers. Finally, after a chaplain intervened, the four other soldiers were charged and court-martialed. Employing a virtuoso level of filmmaking craft, De Palma dramatizes an environment where this kind of atrocity is perhaps inevitable. The young men have been thrust into circumstances in which they can be killed at any moment, and often cannot tell the difference between the enemy and those they are defending. Their only source of hope is their youthful bravado, but the experience of war will always rub their noses in a sense of helplessness. Bravado may curdle into macho posturing, and occasionally into a predatory need to assert dominance over others without any consideration for right and wrong. War can be a test of moral strength, and the picture takes one right to the heart of the crucible the victimization of the woman represents. In the film's most devastating moments, a viewer is seared with the misery of knowing that despite a refusal to do wrong, it may also be impossible to do right. Michael J. Fox is ideal as the story’s hero. His knack for audience rapport could not be stronger, and his talent for verbal double takes, masterfully used in his comic roles, is equally effective in conveying the character’s horror. His small stature is a particular advantage in this role. A viewer is acutely conscious of the character’s vulnerability to go-along-to-get-along bullying, and it makes his ability to stand his moral ground all the more impressive. Sean Penn, who plays the squad leader, is erratic. He’s terrific in the film’s first act. One feels the character’s capacity for heroism, and Penn powerfully takes the viewer inside the moment he is broken. It’s a quiet scene of the character shaving, and his eerie, dead-looking eyes let one know he’s on the edge of madness. It’s one of the finest moments Penn has ever played. But Penn falters in the other two acts. There’s no tension in the angry, theatrical bluster he affects, and he’s repellent as both character and actor. The film has other flaws, including a misconceived framing sequence set after the war, and an award-bait speech Fox’s character delivers at the start of the third act. But despite these, it is one of the finest war dramas ever made, and a high point of Brian De Palma’s career. The cast also includes Thuy Thu Le, John Leguizamo, John C. Reilly, Don Harvey, Sam Robards, Ving Rhames, and Dale Dye. The elegant cinematography is by Stephen H. Burum. Ennio Morricone provided the haunting score. David Rabe based the script on the account of the Hill 192 incident by journalist Daniel Lang, first published as an article in The New Yorker.

Sunday, August 19, 2018

Short Take: Do the Right Thing

Do the Right Thing, written and directed by Spike Lee, is one of the most ambitious films of the 1980s. It is also one of the most accomplished. The story is set on a block in Bedford-Stuyvesant, a predominantly African-American neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York. It's a punishingly hot Saturday in August. Lee, working in an impressionistic slice-of-life mode, follows the comings-and-goings of a multitude of characters from that morning until early the next day. He entertainingly renders the friendly sides of their relationships, but he also captures the tensions between them, which come to the fore as ego battles of varying degree. The conflicts frequently have a racial dimension. The Italian-Americans who own and operate a pizzeria, the Korean-Americans who run a corner store, the white yuppie who recently bought a local brownstone--all become a target of hostility from African-Americans in the neighborhood, and they often give as good as they get. Most of the confrontations are minor: they briefly swell and then recede, and everyone goes about their business. But that night, one of these petty stand-offs escalates into violence. When it ends, there are only losers: a man is dead, and a business has been destroyed. Lee, with remarkable artistry, dramatizes the subtlety with which racial hostility can pervade everyday life, and how the violence it occasionally inspires can seem to erupt out of nowhere. The film is startlingly incisive, and one may find oneself mulling it over for some time after the closing credits roll. The acting ensemble--Lee himself, Danny Aiello, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Richard Edson, Giancarlo Esposito, Samuel L. Jackson, Bill Nunn, Rosie Perez, John Savage, John Turturro, and others--is outstanding. Ernest Dickerson's cinematography powerfully captures the sweltering summer atmosphere. Bill Lee, the director's father, contributed the fine jazz score.

Friday, August 17, 2018

Short Take: Henry & June

Henry & June is director Philip Kaufman's gorgeously realized valentine to the authors Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin, and to 1930s Paris as well. When the film begins in 1931, Nin (Maria de Medeiros) is an aspiring writer who lives outside Paris with her husband Hugo (Richard E. Grant). They're both from the United States, and one day Hugo brings some American acquaintances home for lunch. One of them is Miller (Fred Ward), who lives off the good will of others while working on Tropic of Cancer, the autobiographical novel that will become his masterpiece. He's a bum, but he's a funny, erudite, and expansive fellow, and Nin is entranced with him. She also becomes entranced with his wife June (Uma Thurman), who comes to visit from New York a few weeks later. Miller, though, becomes the most central to her life, particularly after they begin an affair. The film is about Nin's awakening to his more Bohemian temperament, and his openness to experience of all kinds. She also comes to share his obsession with June's narcissism and emotional distance. Kaufman sets Nin's journey and epiphanies in a romanticized Depression-era Paris that's a gritty playground of art, artists, and, it must be said, just about every flavor of sex. The film portrays writing as central for both Nin and Miller, but there is always time to step out to see the latest films by Dreyer and Buñuel, or to help the great photographer Brassaï take his pictures of the Paris demimonde, or just to enjoy wine and laughter with friends at a neighborhood bistro. Kaufman doesn't shy from presenting more wanton pursuits as well. For those enamored with this period of art and literature, the film is a happy dream come to life. Kaufman's Nin and Miller are marvelous guides to this world. Fred Ward wonderfully embodies the Miller who comes across in the author's books. He makes one feel Miller's appetites and joys, as well as the anger that fires the author's sharply caricatural wit. Maria de Medeiros is perfection as Nin. (Nin's second husband was so struck by de Medeiros' performance that he reportedly saw the film every day it played in theaters.) She seems to effortlessly convey Nin's refinement, her naughty joy at throwing off propriety's shackles, and even the occasional cunning when she manipulates others to get what she wants. Grant and Thurman don't make as strong an impression, but everyone is upstaged by Kevin Spacey's hilarious turn as Miller's apartment-mate, a wannabe writer who swears everybody is plagiarizing him. The sumptuous, deep-toned cinematography is by Philippe Rousselot. The terrific production design is by Guy-Claude François, and Thierry François provided the equally impressive costuming. The script is credited to Kaufman and his wife Rose. The source material is Nin's unexpurgated diaries.

Thursday, August 16, 2018

Short Take: Before Sunrise

Before Sunrise, directed by Richard Linklater, is as sweet a love story as one will ever see. An American in his early 20s (Ethan Hawke) is taking a train from Budapest to Vienna, where he’s scheduled to catch a flight back to the United States. He meets a French woman his age (Julie Delpy) who’s heading to Paris, and the two strike up a conversation. Once in Vienna, he convinces her to disembark with him. His plane doesn’t leave for another day, and she can catch another train to Paris in the morning. The film follows them for the next several hours as they walk and talk the night away. The screenplay, by Linklater and Kim Krizan (with uncredited contributions by Hawke and Delpy), has no central dramatic conflict. It just delicately chronicles the pair’s conversations as their rapport deepens and they fall in love. Linklater and the two actors give it a marvelous pace, and the picture has a gentle momentum. Things start out light and funny, but by the end, one is caught up in the characters’ terror at the prospect of never again seeing the other. No film has ever dramatized the experience of falling in love so well. Lee Daniel provided the cinematography. The editing is credited to Sandra Adair. The film was followed by two sequels. The first, 2004’s Before Sunset, is an even richer effort.

Short Take: Great Expectations (1998)

Director Alfonso Cuarón's modern-day Great Expectations is a fine, and occasionally magical, reworking of the Charles Dickens novel. The screenplay, credited to Mitch Glazer, moves the story to the late-20th-century United States. In the prologue, a working-class boy, who lives with his uncle (Chris Cooper) on Florida's Gulf Coast, is kidnapped by a fugitive convict (Robert De Niro) and forced to help him with his escape. Shortly thereafter, a wealthy local spinster (Anne Bancroft) arranges for the boy to be a companion for a beautiful niece the same age. The two (played from adolescence on by Ethan Hawke and Gwyneth Paltrow) are constants in each other's life for the next several years. They part ways when she leaves for college. He has fallen in love with her, but she doesn't quite reciprocate his feelings. Years later, he's put her behind him, and is working alongside his uncle as a fisherman and handyman. That's when his life is upended. He was an aspiring artist as a boy, and an unknown benefactor has arranged for him to move to Manhattan and prepare a gallery show of his work. Once there, he enters high-society circles and meets up again with the niece. This time, he is determined to win her heart once and for all. He also encounters the convict, whose revelations forever change his perception of his life. Cuarón and Glazer revise aspects of the book beyond the setting, such as making the protagonist an aspiring artist. (In the novel, he becomes a member of the idle rich.) But they also do powerful justice to the novel's emotional hooks, particularly the class insecurity that both gives the protagonist his ambition and is behind his worst behavior. Visually, the picture is gorgeous. Dickens' work, despite its social-realist trappings, has a distinct fairy-tale quality. Cuarón, working with production designer Tony Burrough and the master cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, saturate the imagery with that tone. The Florida scenes have a verdant, near-Edenic look, with the spinster's mansion seeming as if nature had all but reclaimed it. The film's Manhattan has a dreamlike Gothic quality, particularly in the nighttime scenes. The protagonist's apartment appears firelit, and the city outside is like an enchanted forest. The cast is a mixed bag. Ethan Hawke and Gwyneth Paltrow are disappointingly bland. (Jeremy James Kissner and Raquel Beaudene, who play the characters as children, are far more vivid.) Anne Bancroft turns the spinster into a campy Carol Channing impression. Robert De Niro is fine in terms of his individual scenes, but the performance doesn't add up to a coherent whole. Chris Cooper is the strongest of the players; he makes the uncle a grounded and affecting presence. (The scene where the uncle shows up uninvited to the gallery show is the most wrenching in the film.) One may also find Cuarón's handling of sex a bit too explicit. But it's an enchanting effort overall, and its daring makes it among the finest Dickens adaptations on film. The protagonist's artwork is by the Italian painter Francesco Clemente.

Wednesday, August 15, 2018

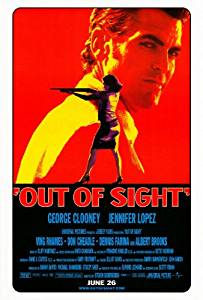

Short Take: Out of Sight

Out of Sight, directed by Steven Soderbergh, is a crackerjack entertainment. Based on the novel by Elmore Leonard, it’s both romantic comedy and crime drama, but the romantic comedy dominates. Serial bank robber Jack Foley (George Clooney) breaks out of a Florida prison, and as part of the escape, he is forced to briefly abduct a U. S. Marshal (Jennifer Lopez). The two are locked together in a car trunk during his getaway--probably the oddest meet-cute in Hollywood history--and they fall in love. They can’t stop thinking about each other afterward. He’s off to Michigan to pull the proverbial one last score, and she’s hot on his trail, but it’s not clear whether she’s out to capture him, romance him, or both. The thought of romance appeals to him, and he lets her stay close, but not close enough to make an arrest. (The film’s big romantic moment is the one time he decides to take his chances.) Clooney and Lopez have terrific chemistry, and neither has ever been better on screen. Both radiate intelligence, and her sexy no-nonsense toughness perfectly complements his trademark roguish charm. The screenplay, credited to Scott Frank, retains the novel’s sharp, witty dialogue and its terrific character ensemble. Each member of the large supporting cast--Nancy Allen, Albert Brooks, Paul Calderón, Don Cheadle, Viola Davis, Dennis Farina, Luis Guzmán, Samuel L. Jackson, Catherine Keener, Ving Rhames, Steve Zahn--gets a chance to shine, and they shine bright. Soderbergh’s direction is sleek, stylish, and never in a hurry. He seems to know a viewer wants to enjoy these characters for as long as possible. When he makes a point of showing his directorial hand, as he does with the film’s editing flourishes, the effects tend to be in the material’s spirit: both funny and romantic. Elliot Davis provided the cinematography, which is color-coded to the Florida, Michigan, and Texas locales. The editing is credited to Anne V. Coates. The musical score is by David Holmes.

Tuesday, August 14, 2018

Short Take: The Matrix

Too many have taken The Matrix way too seriously. The philosophical mumbo-jumbo it wears on its sleeve—little more than Plato’s Allegory of the Cave as filtered through Philip K. Dick—is tony decoration for the pulp material. It’s not anything profound. But the film is still a masterpiece of the science-fiction adventure genre. The Wachowskis, the sibling duo who wrote and directed, have created a stylish cyberpunk mash-up of Dick’s postmodern mystery-sf fiction with superhero comic books and video games. They season it with leather-heavy goth couture and fight scenes inspired by East Asian martial-arts movies. The story’s hero, nicknamed Neo (Keanu Reeves), has two challenges. The first is to solve the mystery that defines the reality around him. The second is to embrace his destiny as the messiah of the film’s dystopian world. Along the way, he joins up with a band of revolutionaries led by Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne), who are determined to help him find his way. The film’s glory is its virtual-reality action sequences, where the only limits are the characters’ imaginations. These scenes are terrifically well-staged and edited, and shot in a hyperreal manner that makes the film look like nothing that had come before. It all adds up to a thrilling roller-coaster ride, and perhaps the finest adventure film of the 1990s. The cast also includes Carrie-Anne Moss, Hugo Weaving, and Joe Pantoliano. Dick Pope provided the cinematography, and the editing is by Zach Staenberg. John Gaeta designed the innovative visual effects. Two pompous, overblown sequels followed.

Sunday, August 12, 2018

Short Take: The Paper Chase (TV series)

The 21st century has ostensibly provided a renaissance in television drama. The most celebrated of the current breed of TV series are defined by a greater reliance on adult themes, an effort to develop the material in a more novelistic manner, and the willingness to end a show when it has run its proper course. Ratings success no longer means a series will continue indefinitely. A significant precursor to this trend is The Paper Chase. Based on a novel by John Jay Osborn, Jr., as well as its 1973 feature-film adaptation, the show debuted in 1978. The showrunner was Robert C. Thompson. The main character was James Hart (James Stephens), a law student at an elite East Coast university. (The school is unnamed in the series, but the novel and the feature film were set at Harvard.) The show followed Hart and his schoolmates as they navigated the demands of law school. Especially notable was Hart’s dealings with Charles Kingsfield (John Houseman), a renowned contract-law professor who inspired both fear and awe in Hart and the other students. The series only lasted a season on network television, but it had attracted a devoted following. In 1983, the Showtime cable network began new episodes, with Lynn Roth taking over as showrunner. It was under Roth that the show fully came into its own. Over the next three years, it fully explored the nexus between adolescence and adulthood that defines the traditional-student experience in higher education. As the students were of graduate-school age, their behavior did not tend towards the juvenile. The elite-university setting also meant the students were quite ambitious and competitive, which gave their responses to their various challenges a compelling intensity. The writing was unfailingly intelligent, and the performances of Stephens, Houseman, and the other cast members always lived up to it. Houseman, who had won an Oscar for playing Kingsfield in the feature film, was especially memorable. Watching him, one always understood Kingsfield's ability to intimidate his students, but also the deep respect he inspired in them. Every episode of the series was something to look forward to. That said, one couldn’t help but appreciate how the show came to an end. Each of the first three seasons had corresponded to a year of the law-school curriculum. The short, six-episode final season brought the series to its natural finish: the graduation of Hart and his classmates. One hated to see the show conclude, but one knew this was being true to the material. The series is one of the finest television dramas ever produced, and perhaps the richest depiction of university life anywhere.

Short Take: Oklahoma! (1999)

If I had to pick a least-favorite movie genre, it would be screen versions of Broadway musicals. The sins of these films are many: hackneyed stories and characters; awful pacing; over-elaborate sets and costumes; bombastic musical arrangements; insipid song lyrics; actors of highly variable singing and dancing abilities--the list goes on. The 1999 film version of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II's Oklahoma!, which debuted in the United States on television in 2003, is a lovely exception. It shows the best way to make these pictures is to keep things simple and appropriately cast. The film is a modestly shot and edited treatment of the stage production that played on London's West End in 1998. The original play is arguably Rodgers and Hammerstein's best effort. (It was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize in 1944) The story is a straightforward romantic comedy, set in 1906 Oklahoma. Two farmhands, one cheerful and optimistic, the other surly and obsessive, vie for the hand of a rancher's daughter in marriage. Trevor Nunn, who directed both the stage production and the film, keeps the sets, costumes, and musical arrangements rather spare. The charm of the story isn't smothered by the weight of the presentation. The performers and musical numbers are allowed to breathe, and the film has a happy atmosphere comparable to the best of the Fred Astaire, Judy Garland, and Gene Kelly vehicles of 1930s, '40s, and '50s. Hugh Jackman, who plays Curly, the more likable of the two farmhands, is a particular delight. He has a wonderfully sunny presence, a gorgeous baritone singing voice, and phenomenal grace as a dancer. Those who only know him from his Hollywood roles, namely the antihero Wolverine in the X-Men films, will find his performance astonishing. Jud Fry, Curly's romantic rival, is played by Shuler Hensley, who brings the part a striking touch of menace. Josefina Gabrielle plays Laurey, the rancher's daughter, and Maureen Lipman steals every scene she's in as Laurey's Aunt Eller. Susan Stroman provided the excellent choreography, on best display in the dream-sequence ballet scene. The film's only conspicuous flaw is the inclusion of cutaway shots to a theater audience ostensibly watching the play. It's the visual equivalent of a TV laugh track.

Wednesday, August 8, 2018

Short Take: X2: X-Men United

Live-action film adaptations of costumed-superhero comic books have been around since the 1940s. In the 21st century, they've become a mainstay of the popular culture. The best of the new millennium's breed is perhaps director Bryan Singer's X2: X-Men United, the second film in the X-Men franchise. The Marvel Comics property was created in 1963 by editor Stan Lee and cartoonist Jack Kirby. Over the years, there was considerable development and several key characters added by others, most notably comics scriptwriter Chris Claremont. The premise is that humanity has reached the next stage of evolution. A new subspecies, called mutants, is coming to the fore. The mutants have varied superhuman powers, and non-mutant humans view them with concern and often fear. Several mutants have embraced assimilation, and their leader is Charles Xavier (Patrick Stewart), a wheelchair-bound benefactor who provides other mutants with a covert haven and school. Xavier's opposite number is Magneto (Ian McKellen), a former friend and ally who leads a revolutionary faction dedicated to mutant rule over the world. X2: X-Men United picks up where the initial X-Men film, also directed by Singer, ended. The story has the two groups joining forces to combat a military scientist (Brian Cox) committed to mutant genocide. Singer delivers a level of spectacle that not only ranks the first film's, but that of the comic books as well. Several scenes, such as Magneto's escape from prison, have a darkly magical grandeur. The more conventional action set pieces are also terrific. Singer has a gift for emotionally charged metonymy, and he uses it to give the quieter character scenes their distinction. X2: X-Men United's most powerful moment, built around the handling of a cigarette lighter, has no other action in it. Magneto recruits a troubled teenager to his cause, and Singer, using the lighter as both prop and trope, eloquently dramatizes the ability of a charismatic megalomaniac to sway the disaffected. The large cast also includes Shawn Ashmore, Halle Berry, Alan Cummings, Bruce Davison, Hugh Jackman, Famke Janssen, Anna Paquin, Rebecca Romijn-Stamos, and Aaron Stanford. The finely woven screenplay is credited to Michael Dougherty, Dan Harris, and David Hayter, working from a story by Hayter, Singer, and Zak Penn. John Ottman, who composed the film's score, also provided the crisp, mosaic-style editing.

Sunday, August 5, 2018

Short Take: Used Cars

Used Cars, directed by Robert Zemeckis, is a great slapstick comedy, and wonderfully free of sentimentality. The rule of the film’s humor is that everything is corrupt, and everybody is out to fleece everyone else. Jack Warden plays twin brothers who own competing used-car lots across the street from each other in Arizona. The brother who owns the more upscale lot is trying to put the other out of business, but he’s always thwarted. The usual obstacle is the other brother’s head salesman (Kurt Russell), a resourceful fast-talking charmer who always stays one step ahead of the various schemes. He also counters them with a few of his own. The rivalry between the two businesses ultimately escalates into all-out war. The most hilarious set piece has one lot blowing up the other’s inventory in a live TV commercial. The brother who owns the upscale lot only gets the upper hand when his niece (Deborah Harmon) takes over her father’s business. That sets off a chain of events that climaxes with the grand comic spectacle of an army of clunkers racing across the desert to save the day. It probably goes without saying, but the film also gets plenty of laughs from the various salesman scams throughout its running time. Kurt Russell is a terrific comic lead. No sensible person would trust his character further than they could throw him, but he’s immensely likable, and he gives the film a good deal of its high spirits. Jack Warden is hilariously cartoonish as the more ruthless of two brothers, and pleasantly down-to-earth as the other. The cast also includes Gerrit Graham, Frank McRae, Al Lewis, Michael McKean, and David L. Lander. The film’s great scene-stealer is the second brother’s pet beagle Toby. The script is by Zemeckis and producer Bob Gale. Donald M. Morgan is credited with the bright, beautifully composed cinematography.

Short Take: Before Sunset

Before Sunset, director Richard Linklater’s 2004 follow-up to his 1995 Before Sunrise, is a lovely, daringly made film. The story has the first film’s lead characters (Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke) meeting in Paris nine years later. Now in their 30s, the two are as erudite and talkative as ever, and they once more fall in love. The difference is that this time, their feelings have none of the purity and naïvete of youth. Their rapport is now colored by the disappointments and anxieties that come with the experiences of being an adult. The script, by Linklater, Kim Krizan, Hawke, and Delpy, is remarkably fluid in its handling of the shifts from happiness to doubt and back again. In keeping with the first firm, it’s also enjoyably wry in its treatment of the characters’ ostensibly pithy perspectives on life and love. The film seems to recognize this talk is simply how these two highly verbal characters make contact. Their pretentiousness is kept light and funny, and the film never makes the mistake of treating it as actual wisdom. Linklater’s directing, along with Delpy and Hawke’s performances, make for a breathtaking high-wire act. The film is a series of long-take tracking shots as the characters talk their way across Paris. Every beat, nuance, and shift in tone has to be played perfectly or the picture would fall apart. The director and the two stars pull it off, and it’s thrilling to see. The attractive open-air cinematography is by Lee Daniel.

Before Sunset, director Richard Linklater’s 2004 follow-up to his 1995 Before Sunrise, is a lovely, daringly made film. The story has the first film’s lead characters (Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke) meeting in Paris nine years later. Now in their 30s, the two are as erudite and talkative as ever, and they once more fall in love. The difference is that this time, their feelings have none of the purity and naïvete of youth. Their rapport is now colored by the disappointments and anxieties that come with the experiences of being an adult. The script, by Linklater, Kim Krizan, Hawke, and Delpy, is remarkably fluid in its handling of the shifts from happiness to doubt and back again. In keeping with the first firm, it’s also enjoyably wry in its treatment of the characters’ ostensibly pithy perspectives on life and love. The film seems to recognize this talk is simply how these two highly verbal characters make contact. Their pretentiousness is kept light and funny, and the film never makes the mistake of treating it as actual wisdom. Linklater’s directing, along with Delpy and Hawke’s performances, make for a breathtaking high-wire act. The film is a series of long-take tracking shots as the characters talk their way across Paris. Every beat, nuance, and shift in tone has to be played perfectly or the picture would fall apart. The director and the two stars pull it off, and it’s thrilling to see. The attractive open-air cinematography is by Lee Daniel.

Saturday, August 4, 2018

Short Take: The Bourne Supremacy

The Bourne Supremacy, the first of director Paul Greengrass's sequels to Doug Liman's 2002 The Bourne Identity, is richer and more powerful than its predecessor. It takes place approximately two years later. Jason Bourne (Matt Damon), the fugitive CIA assassin introduced in the first film, is in hiding in India. He is still struggling with the amnesia about his life before the first film's events. In Berlin, an informant and a CIA investigator are shot to death just as the first is about to reveal information about a traitor inside the agency. Shortly thereafter, Bourne sees a loved one killed by a man (Karl Urban) he mistakenly believes is a CIA operative. Bent on revenge, he returns to Europe to find the agency personnel he thinks are still dogging him. It lands him right in the crosshairs of the deputy director (Joan Allen) investigating the Berlin murders, and while eluding her, he discovers his connection to the treason the pair in Berlin died trying to expose. The traitor is found, and the murderer from India confronted, but not before Bourne realizes his violent methods and quest for revenge are a betrayal of what led him to abandon the assassin's life. The script by Tony Gilroy, the principal screenwriter on the first picture, takes that film's theme of moral awakening to a more profound level. It's not enough to recognize one's reprehensible actions and put them behind one. A moral compass also means recognizing one's propensity for that conduct and keeping it in check. One must also repent to those victimized and try to atone. Paul Greengrass builds on the first picture's existential tone with darker, grubbier visuals and a jumpcut-editing approach that gives the film a stunning immediacy. The action sequences, particularly a harrowing car chase through the streets of Moscow (the setting of the film's third act), easily top the excitement of those in the first picture. It's a terrific adventure movie, and one of the best films of the new millennium. Franka Potente, Brian Cox, and Julia Stiles reprise their roles from the first picture. Oliver Wood also returns as cinematographer, although one would never know it from the look of the two films. The dazzling editing is credited to Christopher Rouse and Richard Pearson. The film is nominally adapted from the novel of the same name by Robert Ludlum, but they have next to nothing in common.

Short Take: The Bourne Identity (2002)

In The Bourne Identity, director Doug Liman achieves a near-perfect synthesis of the fanciful espionage adventures of James Bond with the more grounded spy novels of John le Carré. Liman’s starting point was the Cold War pulp spy novel by Robert Ludlum. But he told screenwriter Tony Gilroy not to read it. He instead gave Gilroy a brief description of the material and told him to present it in a way that fit a post-Cold War setting. The two subverted the novel into something far more resonant. The premise is much the same. The main character (Matt Damon) is an amnesiac gunshot victim fished out of the ocean near Marseilles. The only clue to his identity is a Swiss bank account number implanted in his hip. At the bank in Switzerland, he learns his name is Jason Bourne. He also discovers he has an amazing array of skills, including knowledge of multiple languages and a near-superhuman level of combat acumen. He then finds himself on the run from pursuers out to capture or kill him, with only Marie (Franka Potente), a young woman he just met, for help. His goals are to elude his pursuers as long as possible, and to hopefully learn the full truth of who he is. (He's a CIA assassin.) But the premise is where the similarities between the novel and the film end. Ludlum just offered a standard pulp adventure in which the amnesiac hero has to prove himself innocent of wrongdoing. The film is an existential journey of moral awakening. It also indicts covert intelligence work as a corrupt ends-justifies-the-means cesspool. Liman and Gilroy accomplish all this in the context of a thrilling adventure movie. The action sequences are first-rate. Part of the excitement comes from Liman keeping them models of clarity, and all are rooted in dramatizing Bourne’s resourcefulness. They sometimes get a little too fanciful for the gritty tone Liman strives for, but he generally keeps the action grounded in realism. Matt Damon is superb in the lead. The brawny physique and the deliberate, assured movements leave no doubt about Bourne’s efficiency when it comes to violence. One sees the boyish features that alternate between child-like innocence and a battle-hardened determination, and one knows Bourne became an assassin without ever understanding quite what happened. One also sees his expressive eyes, which Damon uses to evoke the moral intelligence starting to break through. The supporting cast, which includes Franka Potente, Chris Cooper, Brian Cox, Adewale Akkinuoye-Agbaje, and Julia Stiles, is uniformly excellent. The standout is probably Clive Owen, whose character questions a little too late if the sacrifices of espionage work are worth it. The cinematography is by Oliver Wood, and Saar Klein provided the terrific editing. William Blake Herron collaborated with Tony Gilroy on the screenplay.

Friday, August 3, 2018

Short Take: Children of Men

“Very odd what happens in a world without children’s voices.” A character says this about midway through director Alfonso Cuarón’s spectacularly realized dystopian thriller Children of Men. What happens is the world goes mad. The film is set in the England of 2027, 18 years after the last infant has been born. Much of the planet has been devastated by war, and England is one of the few places that still maintains some level of peace and order. As a result, it’s become a destination for refugees from around the world. The country's response is draconian. It is now more or less under martial law, and the chief responsibility of the ubiquitous soldiers is to round up the never-ending flood of immigrants. Pockets of the citizenry have gravitated to the false hopes of revolutionary groups and religious cults. Most, though, are like the film’s protagonist, Theo Faron (Clive Owen): just blankly going through the motions of jobs that don’t seem to matter anymore. But one day Theo’s ex-wife (Julianne Moore) turns up seeking his help in getting a transit visa to the seashore. Before long, he’s caught up in an effort to get the first pregnant woman in 18 years (Clare Hope-Ashitey) to safety outside the country. This context is the stage for one of the most gripping adventure films ever made. Cuarón’s vision of the future is bleak, but the details are so suggestively presented that one always wants to know more about the world he presents. The key action set pieces, particularly the effort to locate the young mother in a besieged seaside town, are so breathtaking they leave one in awe. Owen’s role--the embittered cynic who becomes a heroic man of action--is a bit of a cliché, but he plays it with conviction, nuance, and considerable charisma. Emmanuel Lubezki provided the bravura cinematography. The extraordinarily detailed production design and set decoration are by Jim Clay, Geoffrey Kirkland, and Jennifer Williams. The script, based loosely on the novel by P. D. James, is credited to Cuarón, Timothy J. Sexton, David Arata, Mark Fergus, and Hawk Ostby.

Thursday, August 2, 2018

Film/TV review: The Practice: The Final Season

By 2003, after over 20 years of working, James Spader was firmly established as a cult actor. His specialty was upper-class scoundrels, but he was also able to evoke an earnestness that traded the notes of corruption for gravitas. He could capably play both heroes and villains, and he often did so with a wryness that kept one attentive. There was also that voice: a smooth, resonant drawl that showcased a masterful sense of timing. Every phrase a writer provided Spader became distinctively his own. He was a bright spot in almost everything he appeared in, from his villain roles in Pretty in Pink and Wolf, to the more sympathetic protagonists of Jack’s Back (his best performance in theatrical features), or sex, lies, and videotape and White Palace. The only disappointment for his fans was that he never quite seemed to find the role where everything came together.

Enter David E. Kelley and The Practice.

Kelley, a one-time lawyer, had first come to prominence in the late 1980s as showrunner and head writer for most of the first five seasons of the L. A. Law TV series. He was always ambivalent about the show’s glamorous treatment of attorneys, and in 1997 he launched The Practice, a gritty portrayal of the sordid underside of the legal profession. Kelley set the series at a small Boston law firm specializing in criminal-defense work, and he built the episodes around conflicts between legal ethics and personal morality. Much of the drama came from the characters sacrificing their decency in the name of the ostensibly higher calling of practicing law. This thematic hook, combined with Kelley’s acute social consciousness (and his occasional forays into absurdist humor), made The Practice perhaps the finest legal melodrama in the history of series television.

But after five seasons, The Practice seemed to have worn itself out. The stories began showing the slip of their contrivance. The social conscience flattened into sanctimony. Worst of all, the absurdist moments became more pervasive and were generally more silly than bracing. The audience numbers declined drastically during the sixth and seventh seasons. The ABC network was ready to cancel the series, but they agreed to an eighth season if Kelley would substantially cut the production budget. He rethought the show, dropped over half the cast, and introduced a new lead character: a brilliant though self-destructive lawyer named Alan Shore, with James Spader in the part.

The new character allowed Kelley a fresh take on the morality-versus-ethics conflict. In the show’s earlier seasons, the characters were often demoralized by the dilemmas the conflict posed. Alan Shore wasn’t demoralized at all. He horrified the other characters by gleefully trampling ethical norms, although it was invariably in pursuit of moral ends. Despite his actions and his slick, sleazeball manner, Shore had a profound sense of right and wrong. It might have been more profound than most, because it wasn’t encumbered by concerns about propriety. The suspense of the plotting was no longer rooted in dread of the moral depths the characters might stoop to; it was now in seeing the preposterous lengths Shore was willing to go. But whether he was getting a spiteful criminal charge against a homeless man dropped through a deal involving insurance fraud, or negotiating a settlement in a wrongful-death suit by selling smoking-gun evidence to the defendant's attorney, he almost always got justice for his clients.

Alan Shore is the best role James Spader has ever had, and he played it with relish. The lines Kelley gave the character were slyly sardonic and often outright insolent. Spader’s crack comic timing made them never less than hilarious. Building the stories around Shore’s antics often turned the show's melodrama into farce, and Spader danced with it every step of the way. But Spader was at his best when he turned the humorous tone back to seriousness. He has a genius for playing the scoundrel, but his talent for patrician gravitas runs almost as deep. When Shore stopped the shenanigans and held forth on right and wrong, Spader made him as eloquent a voice of moral authority as one will ever hear. The performance earned James Spader the year's Primetime Emmy for Best Leading Actor in a Drama Series. It was richly deserved.

It’s not clear Kelley immediately recognized how much Spader and Alan Shore were subverting the series. The season’s eleventh episode, “Police State,” is a searing treatment of the conniving extremes law enforcement can go to while investigating a crime. It’s in the same vein as the best of the pre-Spader episodes, and it packed a wallop. Alan Shore is on the sidelines for most of the story, but he has a couple of moments center-stage. His trademark effrontery is so discordant one can barely watch. It's easy to understand how one might feel the character and the series' traditional approach were not compatible. Shortly after the episode aired, it was announced the season would be the series' last. Kelley would be developing a new series featuring Spader as Alan Shore, and it would be more in keeping with the tone the actor and character had introduced. The new show came to be titled Boston Legal.

The latter third of the season was given over to the transition to the new series. Shore’s conduct finally gets him fired, and after a wrongful-termination suit, he takes a position at another, more prestigious firm. The most entertaining of the new characters is the firm’s senior partner, an egomaniacal celebrity trial attorney named Denny Crane. (He ends every utterance by saying his name as if it was a signature.) In a masterstroke of casting, Kelley hired William Shatner, perhaps the most pompously self-regarding actor in the history of film and TV. Shatner, though, seemed to have found perspective on his overblown ostentation, and the episodes featuring Crane have several droll laughs at his expense. The role was self-parody, but Shatner happily seemed in on the joke. It was good to see him join James Spader in the Emmy winners circle after the season ended. Shatner won the year’s award for Best Guest Actor.

James Spader and William Shatner weren't the only performers of note. Michael Badalucco, Steve Harris, and Camryn Manheim, the most distinctive members of the show's original cast, maintained their high level of work. The Practice was always known for the terrific contributions of its guest players, and the final season was no exception. Among those featured: Edward Asner, Lake Bell, Jill Clayburgh, Gary Cole, Viola Davis, Rebecca De Mornay, Patrick Dempsey, Lisa Edelstein, Rick Hoffman, Ron Leibman, Elisabeth Moss, Chris O'Donnell, Sharon Stone, Holland Taylor, and Betty White. Sharon Stone won the year's Primetime Emmy for Best Guest Actress, and Betty White was with her among the nominees.

Boston Legal debuted in the fall of 2004. The few episodes I watched were disappointing. The new series seemed to go too far in shifting to a more humorous approach. The grit was gone, and the Alan Shore character began to feel like schtick for both Spader and Kelley. I found it rather insipid.

That opinion isn’t a consensus one. During its five seasons, Boston Legal earned a Peabody Award and an Emmy nomination for Best Drama Series. Spader was even more celebrated for playing Alan Shore on the newer show than on The Practice. The role won him two more Best Actor Emmys. He also received several accolades he was passed over for the first time around. He’s gone on to do more fine work, most notably as the criminal mastermind Raymond Reddington on the espionage action-adventure series The Blacklist. But that final season of The Practice is where James Spader fully came into his own, and I think it was the finest stage for one of my favorite actors.

Enter David E. Kelley and The Practice.

Kelley, a one-time lawyer, had first come to prominence in the late 1980s as showrunner and head writer for most of the first five seasons of the L. A. Law TV series. He was always ambivalent about the show’s glamorous treatment of attorneys, and in 1997 he launched The Practice, a gritty portrayal of the sordid underside of the legal profession. Kelley set the series at a small Boston law firm specializing in criminal-defense work, and he built the episodes around conflicts between legal ethics and personal morality. Much of the drama came from the characters sacrificing their decency in the name of the ostensibly higher calling of practicing law. This thematic hook, combined with Kelley’s acute social consciousness (and his occasional forays into absurdist humor), made The Practice perhaps the finest legal melodrama in the history of series television.

But after five seasons, The Practice seemed to have worn itself out. The stories began showing the slip of their contrivance. The social conscience flattened into sanctimony. Worst of all, the absurdist moments became more pervasive and were generally more silly than bracing. The audience numbers declined drastically during the sixth and seventh seasons. The ABC network was ready to cancel the series, but they agreed to an eighth season if Kelley would substantially cut the production budget. He rethought the show, dropped over half the cast, and introduced a new lead character: a brilliant though self-destructive lawyer named Alan Shore, with James Spader in the part.

The new character allowed Kelley a fresh take on the morality-versus-ethics conflict. In the show’s earlier seasons, the characters were often demoralized by the dilemmas the conflict posed. Alan Shore wasn’t demoralized at all. He horrified the other characters by gleefully trampling ethical norms, although it was invariably in pursuit of moral ends. Despite his actions and his slick, sleazeball manner, Shore had a profound sense of right and wrong. It might have been more profound than most, because it wasn’t encumbered by concerns about propriety. The suspense of the plotting was no longer rooted in dread of the moral depths the characters might stoop to; it was now in seeing the preposterous lengths Shore was willing to go. But whether he was getting a spiteful criminal charge against a homeless man dropped through a deal involving insurance fraud, or negotiating a settlement in a wrongful-death suit by selling smoking-gun evidence to the defendant's attorney, he almost always got justice for his clients.

Alan Shore is the best role James Spader has ever had, and he played it with relish. The lines Kelley gave the character were slyly sardonic and often outright insolent. Spader’s crack comic timing made them never less than hilarious. Building the stories around Shore’s antics often turned the show's melodrama into farce, and Spader danced with it every step of the way. But Spader was at his best when he turned the humorous tone back to seriousness. He has a genius for playing the scoundrel, but his talent for patrician gravitas runs almost as deep. When Shore stopped the shenanigans and held forth on right and wrong, Spader made him as eloquent a voice of moral authority as one will ever hear. The performance earned James Spader the year's Primetime Emmy for Best Leading Actor in a Drama Series. It was richly deserved.

It’s not clear Kelley immediately recognized how much Spader and Alan Shore were subverting the series. The season’s eleventh episode, “Police State,” is a searing treatment of the conniving extremes law enforcement can go to while investigating a crime. It’s in the same vein as the best of the pre-Spader episodes, and it packed a wallop. Alan Shore is on the sidelines for most of the story, but he has a couple of moments center-stage. His trademark effrontery is so discordant one can barely watch. It's easy to understand how one might feel the character and the series' traditional approach were not compatible. Shortly after the episode aired, it was announced the season would be the series' last. Kelley would be developing a new series featuring Spader as Alan Shore, and it would be more in keeping with the tone the actor and character had introduced. The new show came to be titled Boston Legal.

The latter third of the season was given over to the transition to the new series. Shore’s conduct finally gets him fired, and after a wrongful-termination suit, he takes a position at another, more prestigious firm. The most entertaining of the new characters is the firm’s senior partner, an egomaniacal celebrity trial attorney named Denny Crane. (He ends every utterance by saying his name as if it was a signature.) In a masterstroke of casting, Kelley hired William Shatner, perhaps the most pompously self-regarding actor in the history of film and TV. Shatner, though, seemed to have found perspective on his overblown ostentation, and the episodes featuring Crane have several droll laughs at his expense. The role was self-parody, but Shatner happily seemed in on the joke. It was good to see him join James Spader in the Emmy winners circle after the season ended. Shatner won the year’s award for Best Guest Actor.

James Spader and William Shatner weren't the only performers of note. Michael Badalucco, Steve Harris, and Camryn Manheim, the most distinctive members of the show's original cast, maintained their high level of work. The Practice was always known for the terrific contributions of its guest players, and the final season was no exception. Among those featured: Edward Asner, Lake Bell, Jill Clayburgh, Gary Cole, Viola Davis, Rebecca De Mornay, Patrick Dempsey, Lisa Edelstein, Rick Hoffman, Ron Leibman, Elisabeth Moss, Chris O'Donnell, Sharon Stone, Holland Taylor, and Betty White. Sharon Stone won the year's Primetime Emmy for Best Guest Actress, and Betty White was with her among the nominees.

Boston Legal debuted in the fall of 2004. The few episodes I watched were disappointing. The new series seemed to go too far in shifting to a more humorous approach. The grit was gone, and the Alan Shore character began to feel like schtick for both Spader and Kelley. I found it rather insipid.

That opinion isn’t a consensus one. During its five seasons, Boston Legal earned a Peabody Award and an Emmy nomination for Best Drama Series. Spader was even more celebrated for playing Alan Shore on the newer show than on The Practice. The role won him two more Best Actor Emmys. He also received several accolades he was passed over for the first time around. He’s gone on to do more fine work, most notably as the criminal mastermind Raymond Reddington on the espionage action-adventure series The Blacklist. But that final season of The Practice is where James Spader fully came into his own, and I think it was the finest stage for one of my favorite actors.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)