Sunday, September 30, 2018

Short Take: Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

The original Invasion of the Body Snatchers, directed by Don Siegel, is a superb science-fiction film, and one of the great Hollywood thrillers. A small-town doctor (Kevin McCarthy) returns home from a convention, and finds that a number of the townspeople are convinced that relatives have been replaced with impostors. He gradually discovers the reason why. Extra-terrestrial plant spores have landed at area farms, where they've grown into seed pods. Once in the vicinity of a sleeping human, a pod creates a perfect physical duplicate as a step towards infecting and taking over the person's mind. In short order, the pod people take over the town, and from there, they plan to take over the world. Screenwriter Daniel Mainwaring, working from the Jack Finney novel The Body Snatchers, delivers a terrific paranoia scenario: the doctor doesn't know whom he can trust, or for how long, in his efforts to escape the town and warn the outside world. Don Siegel knows to keep out of the story's way. The scenes are staged, shot, and edited with a minimum of fuss. There's only one scene of directorial flamboyance: the climactic moments when the doctor runs onto a busy freeway screaming for help. The only other element that goes out of its way to work the audience is Carmen Dragon's fine score, and its passages of screeching violins and rumbling piano keys. Siegel and Mainwaring aren't fancy, but they deliver a grippingly suspenseful roller-coaster ride. The picture also has some spice for middlebrows. It's very easy to read the material as a satirical allegory decrying the conformist culture of the 1950s U. S., and even the Joseph McCarthy-led communist witch-hunts. The cast also features the beautiful Dana Wynter as the doctor's love interest, as well as Larry Gates, King Donovan, and Carolyn Jones. The black-and-white cinematography, which has some fine moments of noir chiaroscuro, is by Ellsworth Fredericks. Robert S Eisen is credited with the editing. A framing sequence, added at the production studio's insistence, features the veteran character actors Whit Bissell and Richard Deacon. The film has been remade three times: a 1978 version with the same title, directed by Philip Kaufman; Abel Ferrara's 1993 Body Snatchers; and Oliver Hirschbiegel's 2007 The Invasion, starring Nicole Kidman and Daniel Craig.

Tuesday, September 25, 2018

Short Take: Black Sunday

Gothic horror made quite a comeback in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The movies produced by England's Hammer Studios were the most popular of the trend, but the Italian film Black Sunday, directed by Mario Bava, was perhaps the best. It begins in 17th-century Moldavia, when a witch (Barbara Steele) and her lover (Arturo Dominici) are ritually disfigured and burned at the stake on the orders of her royal brother (Ivo Garrani). She puts a curse on their family, and two centuries later, after a pair of traveling doctors (John Richardson and Andrea Checchi) disturb her tomb, her spirit puts it in motion. Her ultimate goal is to take possession of the young princess (also played by Steele) who resembles her. Visually, the film is a lavish pastiche of Gothic tropes: tangled forests of gnarled, barren trees; castles and crypts in various stages of decrepitude; ground fog everywhere. These, combined with the magnificent chiaroscuro of Bava's black-and-white cinematography, give every scene an eerie, spellbinding quality. Bava sets the stage wonderfully, and he keeps the pulpy horror melodrama briskly paced and suspenseful. True to the genre's form, he also delivers some indelible moments of both grisliness and the uncanny. The saucer-eyed Barbara Steele has a great camera face, and her bold features give the witch's malevolence a fitting hyperbole. Giorgio Giovannini provided the spectacular production design. The screenplay, by Ennio De Concini and Mario Serandrei (with uncredited contributions from Bava, Marcello Coscia, and Dino De Palma), was inspired by the short story "Viy," by Nikolai Gogol. The version of the film available in North America is dubbed into English, using a script translation by George Higgins III. The movie's original Italian title is La maschera del demonio (The Mask of the Demon).

Monday, September 24, 2018

Short Take: Shoot the Piano Player

There's a jazzy, anything-goes spirit to François Truffaut's tragicomic crime drama Shoot the Piano Player. The main character is a one-time concert pianist (Charles Aznavour) who has bottomed out after a family tragedy. Apart from raising his youngest brother (Richard Kanayan), he's retreated from life. He's changed his name, and earns a modest living playing piano with a dance band at a local bar. But beyond that, all he wants is to be left in peace. His past, though, again confronts him. It's in good ways and bad. The good is the waitress (Marie DuBois) who knows who he is, and with whom he falls in love. The bad are the two adult brothers (Jean-Jacques Aslanian and Albert Remy) who get him mixed up in their wranglings with local gangsters. Truffaut does full dramatic justice to the plotting and the protagonist's inner conflicts. But he also treats the story as a springboard for constant arabesques: observational humor, oddball conversations, music and dance numbers, slapstick and romantic comedy scenes, and a bevy of cinematic flourishes. The delight of the film is that the spontaneous atmosphere doesn't distract. It enriches the material. The discords keep one attentive to the rather banal pulp material, and give it a wonderful true-to-life rhythm. The effect is further enhanced by Raoul Coutard's superb documentary-style cinematography. The stars enhance the film, too. Charles Aznavour's hangdog manner and Marie DuBois' down-to-earth dream-girl quality are perfect. The cast also includes Nicole Berger, Michèle Mercier, and Daniel Boulanger. The screenplay, credited to Truffaut and Marcel Moussy, is based on the David Goodis novel Down There.

Sunday, September 23, 2018

Short Take: La notte

Michelangelo Antonioni's La notte has an aching melancholy that turns shattering. It's a portrait of a failing marriage over the course of about a day. It begins with a hospital visit with a terminally ill family friend, and ends with an all-night party at a wealthy industrialist's estate. Marcello Mastroianni plays the husband. He's a successful novelist whose passion for his career is drying up, and it's rotting out his rapport with his upper-class wife (Jeanne Moreau). All that engages him are prospects for sex: a disturbed young woman (Maria Pia Luzi) he encounters in the hospital; a beautiful, intelligent young socialite (Monica Vitti) at the party; and even his wife when she tells him things he can't bear to hear. The film, though, is at its richest when the wife is central, not the husband. The most imaginative sequence is her trek through town after an argument with him. It's a marvelous allegory of nostalgia for her younger days--impulsive childhood pleasures, flirting with random men, and so forth--that ends with her visiting the neighborhood where the couple had their first home. The area is now dilapidated, and she recognizes there's no going back. The most powerful moment is the picture's climax, when, through the wife's reference to past days, the full extent of the husband's dissociation from both his writing and his marriage is revealed. The scene is one of the most devastating in all of film, and Jeanne Moreau's moody elegance has never been more compelling. Mastroianni is the picture's weakest aspect; his performance barely registers. Monica Vitti and the other supporting players complement Moreau much better. Antonioni's masterful command of staging and shot composition is on fine display, and he and cinematographer Gianni di Venanzo give the proceedings a glamorously decadent look. Ennio Flaiano and Tullio Pinelli collaborated with Antonioni on the screenplay.

Friday, September 21, 2018

Short Take: 8½

Federico Fellini's 8½ is an exuberantly imaginative film. The irony is that its subject is creative block. Marcello Mastroianni plays a celebrity film director who has hit a wall with his current project. It's a big-budget science-fiction spectacular. The director has a broad outline in place, and considerable work done on the production trappings, but he can't pull his ideas together and start filming. He tries to take a break and recharge at a luxury spa, but his producer (Guido Alberti) sends the production crew to his hotel to continue their work. Hoping to break out of his rut, he has his mistress (Sandra Milo), and then his wife (Anouk Aimée) visit the spa, too. The film is ultimately about the director coming to terms with his life, and Fellini continually shifts from his current circumstances to flashbacks about his childhood and fantasies about the various people close to him. The brilliantly allegorical fantasy sequences range from the poignant, such as the director's encounter with the ghosts of his parents, to slapstick hilarity, as with the harem set piece in which all the women he knows turn on him. The present-tense scenes are a grand farce, with the director continually trying to fend off collaborators, hangers-on, and wannabes, as well as juggle the presences of both his wife and mistress. The comic high point is when his producer (literally) drags him to a press conference at the project's most colossal set. Fellini hits every note, whether dramatic or comic, with dazzling effectiveness, and the film is gorgeous. Piero Gherari's sets and more outré costuming are wonderfully baroque, and Gianni di Venanzo's black-and-white cinematography is among the most richly beautiful in all of movies. Fellini's marvelous spatial sense and command of movement, both in the staging and camerawork, have never been better. Mastroianni and the rest of the cast are excellent, with Sandra Milo's comic turn as the airheaded mistress being the standout. The film is a delight from start to finish.

Monday, September 17, 2018

Short Take: La Jetée

Writer-director Chris Marker's La Jetée is one of the finest science-fiction films ever made. In a post-apocalyptic Paris, scientists look to the possibilities of time travel to save the human race. After some failed experiments with various prisoners, they settle on one (Davos Hanich), who has a brief, obsessive memory of a woman (Hélène Chatelain) he saw on an airport observation deck as a child. On his trips to the past, he meets the woman, and the two fall in love. His people eventually send him to the future, where he is given their salvation. After he returns, he is offered the choice of permanent return to the past or future. He chooses the past, only to learn that his present will follow with tragedy wherever he goes. The irony is that the tragedy is one he always knew, but never recognized until it was too late. One can never escape the present by losing oneself in other times. This allegorical fable of time, memory, and nostalgic escapism is presented with an extraordinary artfulness. The film, 28 minutes long, is told as a series of still photographs. Spectacle is kept to a minimum. The starkly evocative photos set the stage, and their expressive beauty carries the story along. The stills are a fine metaphor for memory; the flow of experience becomes frozen in the peak moments of happiness, pain, and drama. Marker departs from the photos only once: the few seconds when the woman awakens with her eyes full of love. It's an exquisitely poetic use of the motion-picture form. Jean Ravel provided the beautifully paced editing. The music is by Trevor Duncan, with the choral music directed by Piotr V. Spassky. The story was the inspiration for the 1995 film 12 Monkeys, directed by Terry Gilliam.

Sunday, September 16, 2018

Short Take: Dr. Strangelove

Dr. Strangelove, directed and co-written by Stanley Kubrick, has a fair claim to being the finest satire in all of film. It also has a fair claim to being the finest work of satire ever produced by an American. The film begins when an Air Force general (Sterling Hayden) has a psychotic breakdown, and sends the bombers under his command to attack the Soviet Union with nuclear weapons. The efforts of the U. S. president (Peter Sellers) and his advisors to deal with the situation are frantic. Things are further complicated by the revelation that the Soviets have created a doomsday weapon that will end life on Earth if they are attacked. Kubrick pillories the mindset behind Cold War militarism and strategic concepts such as "mutually assured destruction." One is shown the logic of such thinking, and the efficiency of the operations, but the lunacy of it all is left unmistakable. Giving the apocalyptic absurdity its full due, Kubrick renders the material in the most extreme, grotesquely caricatural terms. The military and government leaders are portrayed as egomaniacal buffoons. It's fitting, as only the greatest of fools could implement such insane tactics. But as incisive as the film is, it is also uproariously funny. The absurdities are heightened with such wit that, regardless of the horror, one cannot help but laugh out loud. Most impressively, the film has not lost its relevance in the Cold War's aftermath. The core lampoon of tough-guy militarism has proved astonishingly enduring, as the culture never seems to stop producing real-life analogues to the film's characters. The cast is wonderful. Peter Sellers plays three roles--the nebbishy president, a British aide to the psychotic general, and the title character--and he makes all three distinct and hilarious. He's almost matched by George C. Scott, who plays the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. This "sane" general is nearly as crazy as the one who launched the attack. But the funniest performance is by cowboy actor Slim Pickens, who plays the officer leading the bombing mission. The character's self-deprecating lines in such grave circumstances would be amusing enough, but the sound of them delivered in Pickens' laid-back Texas drawl has a side-splitting comic edge. The cast also includes Keenan Wynn, Peter Bull, and James Earl Jones. Terry Southern and Peter George collaborated with Kubrick on the screenplay, which takes its plot from George's novel Red Alert. Ken Adam provided the outstanding production design. His "War Room" set is deservedly one of the most famous (and imitated) in movies. The cinematography is credited to Gilbert Taylor.

Friday, September 14, 2018

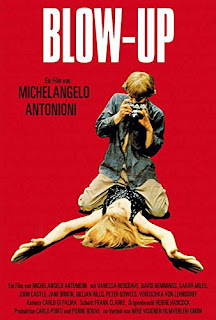

Short Take: Blow-Up

Michelangelo Antonioni is among the most glamour-minded of filmmakers. It’s only fitting that Blow-Up, one of his best efforts, is about a fashion photographer. The fellow (played by David Hemmings) is young, wealthy, handsome, and a minor celebrity. The film is more or less a day-in-the-life portrait. There’s him at work, such as the session with a high-end model that’s hilariously staged as a mock sexual tryst. And there’s him at play: tooling around London in his Rolls Royce convertible; shopping for antiques; having a spur-of-the-moment threesome with a pair of groupies. His life is breezy and hedonistic, and quite enjoyable to watch. A great deal of the pleasure comes from the film’s gorgeous visuals. Antonioni’s distinctive style of shot composition and choreographic staging is on terrific display. Working with cinematographer Carlo di Palma, art director Assheton Gordon, and costumer Jocelyn Rickards, he also gives the picture a bold, colorful Pop look. The story gets some melodramatic spice when the photographer, while developing some random photos, believes he may have inadvertently photographed a murder. There are signs of a conspiracy, and the photographer becomes fixated on finding a woman (Vanessa Redgrave) who may be a key to the mystery. These scenes highlight an undercurrent of priggish hand-wringing about the photographer's carefree attitude and the licentious social atmosphere, but Antonioni doesn’t push it too hard. This section of the film has too much to enjoy on its surface. The sequence in which the photos of the murder are developed is dazzlingly edited and sleekly suspenseful. Hitchcock never did it better. Afterward, the viewer is treated to a club performance by the Yardbirds, and a low-key slapstick encounter with a mime troupe. It’s so entertaining one may not even notice the moralizing. The film is a wonderful showcase for the elegance of Mod style, and it captures the naughty chic of 1960s “Swinging London.” The script, credited to Antonioni, Tonino Guerra, and Edward Bond, was inspired by the Julio Cortázar short story “Las babas del diablo.” Herbie Hancock provided the non-diegetic music.

Thursday, September 13, 2018

Short Take: The Conformist

The Conformist, directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, is one of the few movies where the visuals leave one swooning. That's quite an achievement, but the even greater one is Bertolucci's making this bravura serve the material. The story, set largely in 1938, is about an upper-class Italian (Jean-Louis Trintignant) whose goal, after his troubled upbringing, is to lead a normal life. He's reserved in the extreme, but he's determined to marry, have children, and give them a stable home. The government is controlled by the Fascists, so he becomes a Fascist, and is made a member of the secret police. That's when the life he seeks demands a price. The government orders him to travel to Paris and assassinate a former professor (Enzo Tarascio) whose anti-Fascist activities have forced him into exile. The protagonist uses his honeymoon as a cover, and he renews his acquaintance with the teacher. He also falls in love with the man's wife (Dominique Sanda). The dynamic of the filmmaking is in the contrast between the buttoned-down manner of the protagonist and the often hyperbolic glories of the movie around him. The flamboyant staging and camera movements are as choreographed as a ballet. The Paris locations are used as the grandest of sets. The master cinematographer Vittorio Storaro offers some of the most atmospheric treatments of weather ever seen on film. Ferdinando Scarfiotti makes bold use of Fascist aesthetics in his production design, and his and Storaro's handling of color is gorgeous. The uptightness of the protagonist amid all this splendor is beyond absurd--it's perverse. The women make him seem even more discordant. Dominique Sanda gives a quiet albeit powerful erotic edge to the professor's wife, and Stefania Sandrelli, who plays the protagonist's ditsy bride, is a bubbly comic delight. Jean-Louis Trintignant's fine performance enriches one's view of the protagonist. One can always see the fellow's anxiety in his eyes, posture, and his rather creepy smile. Trintignant plays him with considerable nuance; one can always see his mind working, and while he's at odds with the film's other elements, he's anything but a dead spot on the screen. In musical terms, Trintignant is the percussion that anchors the extravagant melodies Bertolucci plays around him. The script, credited to Bertolucci, is based on the novel by Alberto Moravia. Georges Delerue provided the lively score.

Friday, September 7, 2018

Short Take: The Candidate

The Candidate is probably the single finest movie about American politics, and easily the richest (and funniest) treatment of a political campaign. A professional campaign strategist (Peter Boyle) is looking for a new race to run. He settles on Bill McKay (Robert Redford), a social-activist attorney, as a candidate for U. S. Senator. McKay's innate advantages are considerable. He has the name recognition that comes from being the son of a popular former governor (Melvyn Douglas), and he's exceptionally telegenic--handsome, personable, and well-spoken. McKay initially refuses to run, but the strategist convinces him that the incumbent (Don Porter) is nearly unbeatable, and that frees up the opportunity for a campaign of ideas and principles. McKay's candidacy, though, gains traction, and the closer the race gets, the further McKay is taken from the ideals he sought to promote. Jeremy Larner's breezily cynical script does a terrific job of satirizing the inherent bad faith of most political campaigns, from the hackneyed language of slogans and speeches to hypocritical alliances to the opportunistic exploitation of people and calamities in the effort to gain support. Director Michael Ritchie presents the material in an impressionistic, semi-documentary style that fully captures the mercurial atmosphere that defines politics in the contemporary media age. Robert Redford is marvelous in the lead. His charisma and extraordinary good looks make him seem perfectly cast, but Redford also has a wryness to him, and he uses it to subtly put across McKay's disgust at how the campaign is selling out his dignity. The supporting cast is also strong, with particular kudos to Don Porter for the polished gravitas he gives McKay's opponent. Victor J. Kemper provided the cinematography. The outstanding editing is by Robert Estrin and Richard A. Harris. Ritchie and Redford made uncredited contributions to the script.

Short Take: Chinatown

One of the richest modes of Hollywood filmmaking in the 1970s was taking pulp genres, filtering out the kitschier aspects, and reimagining the material in more realistic terms. What The Godfather did for the gangster film, and McCabe & Mrs. Miller did for the Western, Chinatown does for the private-detective thriller. The defining feature of pulp detectives such as Dashiell Hammett's Sam Spade and Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe is their above-it-all cynicism. (It's also probably their source of appeal for adolescent male readers--of all ages.) Chinatown's protagonist, Jake Gittes (Jack Nicholson), has similar attitudes, but unlike Spade and Marlowe, it isn't romanticized. It defeats him at nearly every turn. He's at least as resourceful as the Hammett and Chandler heroes, but he's still unprepared for the depths of public corruption he uncovers, or for the horrifying secret of the story's heroine (Faye Dunaway). Robert Towne's screenplay is an elegantly woven mix of mystery and psychological drama. Roman Polanski's direction gives every scene a true-to-life rhythm without ever letting the pace go slack. When violence or other sensational elements erupt, they feel integral to the story. There's no pulpiness; those parts never come off as cheaply cathartic or shoehorned in to heighten the pace. The actors live up to the high standard of the script and direction. Jack Nicholson keeps his natural flamboyance in check, and delivers a richly nuanced characterization. He has a viewer all but inside Gittes' thoughts and feelings. Faye Dunaway capably balances the heroine's upper-class poise with her guardedness and near-neurotic anxieties. John Huston, who plays the heroine's father, oozes smarmy malevolence. The rest of the cast, including Diane Ladd, Perry Lopez, John Hillerman, Burt Young, James Hong, and Polanski himself, is note-perfect. The behind-the-scenes artisans do full justice to the 1930s setting. Cinematographer John A. Alonzo, production designer Richard Sylbert, and costumer Anthea Sylbert all turn in first-rate work. The fine musical score is by Jerry Goldsmith.

Short Take: The Godfather, Part II

The Godfather, Part II, directed and co-written by Francis Ford Coppola, is the best kind of movie sequel. It expands and enriches one's view of its predecessor, and it's an engrossing, accomplished work in its own right. The film picks up the story of Mafia lord Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) in the late 1950s, and contrasts it with the experiences of his father as a young man (Robert De Niro). The flashback sequences are the most engaging part of the film. The arc of the father's early life--from orphaned immigrant to New York crime boss--is elegantly structured and beautifully dramatized. The picture does a marvelous job of recreating Manhattan's Little Italy in the early 20th century, and De Niro's finely modulated performance is perfect for the father's balance of judiciousness and brutality. The 1950s sections aren't quite as assured. Coppola doesn't present the various Mafia intrigues as clearly as one might like. But whatever reservations one has are dispelled by the climax. The father's violent methods, always rationalized in terms of family duty, reach their ironic culmination in the ruthless, soullessly vindictive action Michael takes. Family obligations are turned against themselves, and the tragedy of Michael's character assumes even fuller dimensions than it did in the first picture. This is one of the most devastating endings in all of film. The superb cast also includes Robert Duvall, Diane Keaton, John Cazale, Talia Shire, Michael V. Gazzo, Lee Strasberg, G. D. Spradling, Morgana King, and Richard Bright. The beautiful, richly toned cinematography is by Gordon Willis. Dean Tavoularis oversaw the impressive production design. Mario Puzo adapted the scenes of the father's early life from passages in his original novel. The rest of the script is by Coppola.

Sunday, September 2, 2018

Short Take: Lacombe, Lucien

Director Louis Malle's Lacombe, Lucien, set in France during the final weeks of the Nazi Occupation, is a haunting portrait of the banality of evil. The film's greatness is in its refusal to allow for easy judgments. Lucien (Pierre Blaise) is a rural 17-year-old who, in the opening scenes, is denied status and fulfillment everywhere he turns. He works as a janitor at a hospital that's too far from his hometown to make a daily commute. He's less than welcome in his family's home in any case; his father has been imprisoned by the Nazis, and the man his mother has taken up with doesn't want him around. He tries to join the Resistance, but the local leader--his old schoolmaster--considers him too dim to be of use. He then falls in with the local Gestapo, and for perhaps the first time in his life, he is made to feel like he belongs. Malle establishes Lucien as a moral idiot, and that he becomes a Nazi thug for the homeliest of reasons, but the film never asks one to view him with hatred. One sees how out of place he is among the gentry, the bureaucrats, and the hangers-on who make up the local collaborators. He falls in love with a Jewish girl (Aurore Clément) whose family is laying low in the community, and the film deftly renders the class tensions between him and the girl's father (Holger Lowenälder). The father, a bourgeois tailor, seethes at having Lucien, whom he regards as an uncouth hick, both living in his home and sharing his daughter's bed. It's impossible not to sympathize with his anger, but one also recognizes the snobbishness that's partly behind it. One's ambivalence about Lucien is strongest in the pastoral final section. The country-boy hunting and survival skills that made him of such use to the Nazis belonged here, not corrupted by brutalizing his countrymen. And one sees his happiness, particularly with his hearty laughter during a moment with the tailor's daughter. Malle shows the ideal of who Lucien is in this woodland setting, and that, in many ways, he's an innocent brought low by circumstances. The film ends with a brief text epilogue telling what happens to Lucien next. It leaves one torn over whether it's justice or tragedy, and one must ultimately reconcile it as both. Malle wrote the superb script with novelist (and future Nobel literature laureate) Patrick Modiano. He dramatizes it matter-of-factly and with striking intelligence. No implication is glossed over; it's there for all to see. Everything serves the material, from Tonino delli Colli's deep-toned cinematography to the shrewd casting of the non-professional Pierre Blaise in the title role.

Short Take: Taxi Driver

"I'm God's lonely man." Taxi Driver, directed by Martin Scorsese from a script by Paul Schrader, may be as close as films have gotten to the power of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s fiction. It’s fevered and intense, and it fully catches one up in its protagonist’s descent from alienation into madness. The main character, played by Robert De Niro, is named Travis Bickle. He is a 26-year-old former Marine who takes a job as a nighttime cabbie in New York City. He cannot find any kind of rapport with others; he’s so disengaged that the friendly overtures of coworkers make little impression. He becomes infatuated with a pretty campaign worker (Cybill Shepherd), who finds him amusing, but he ultimately can’t help but offend her. Having no outlet for any positive emotion, he grows angrily obsessed with the more squalid aspects of the city, and becomes fixated with saving a 12-year-old prostitute (Jodie Foster). He also becomes fixated with the politician (Leonard Harris) who employs the campaign worker. Scorsese powerfully dramatizes the world as Bickle experiences it. The rhythms of life seem off-kilter and halting. Daylight feels harsh and oppressive, and the night is close to hallucinatory. The city is portrayed as a dizzying, luridly tactile nightmare. Robert De Niro’s performance is one of the greatest in all of film. He takes a viewer inside how disconnected Bickle is, and he makes one feel every tick of the time bomb of resentment, obsession, and violence the character becomes. The terrific supporting cast also includes Peter Boyle, Albert Brooks, and Harvey Keitel. Scorsese has a blistering scene in the role of a deranged cab passenger. But the standout among the supporting players is Jodie Foster, who delivers perhaps the most vivid, nuanced work one will ever see from a child actor. The cinematographer was Michael Chapman, and Bernard Herrmann provided the moody, dissonant score.

Saturday, September 1, 2018

Short Take: Annie Hall

With Annie Hall, writer-director Woody Allen moved away from the fanciful, parodistic mode of his earlier films. He embraced a far more naturalistic approach, with the humor becoming richer, and the material taking on a far greater gravitas. But as strong as the best of his subsequent work was, it was all in the shadow of this pivotal effort. It is probably best described as a comic romance. A New York stand-up comedian (played by Allen) reflects on his life. He touches on his childhood, his Jewish upbringing, and his two failed marriages. But what preoccupies him the most is his up-and-down relationship with the title character (Diane Keaton), an aspiring singer from the Midwest. The story of their affair is a lovely showcase for some of Allen's best observational humor and incidental jokes. The mundane, even homely aspects of a romantic relationship have never been made funnier. Allen's onscreen persona, a nebbishy urban neurotic, is realized with such wit that the portrayal seems like a template for the similar characters in his other films, which can only hope to approximate it. And then there's Diane Keaton. She's charming and hilarious when the relationship begins, but she also lets one see the ditsy, self-deprecating behavior is a mask the character uses to put others at ease. There's a willful, at times cynical woman underneath. It's a rich, rounded characterization, and deservedly Keaton's signature role. The cast also includes Tony Roberts, Paul Simon, and Carol Kane. Allen cowrote the screenplay with Marshall Brickman. There's speculation, sometimes assumed as fact, that the film is a semi-autobiographical treatment of Allen and Keaton's real-life romantic relationship in the early 1970s. Allen denies this, and the known facts of the two's lives bear him out.

Short Take: The Deer Hunter

The Deer Hunter, directed by Michael Cimino, is a powerfully affecting treatment of Americans and the Vietnam War, seen in terms of small-town friendships, quiet patriotism, and masculine pride. It centers on a group of steelworkers from a Russian-American community in Pennsylvania. Three of them (Robert De Niro, Christopher Walken, and John Savage) go off to serve in the Army special forces. The film takes no view of the politics of the war. The men and their loved ones treat service as a matter of simple duty. Grief is the only thought when one of them comes back crippled, and another goes AWOL after a breakdown. The picture is at its most incisive when it explores how the embrace of storybook adventure values, while enabling the three to survive the war, can become profoundly distasteful afterward, and even corrupted into suicidal pursuits. This is far from a perfect film. The scenes in Vietnam are an uncomfortable, even gaudy mix of allegory and pulp, and the portrayal of the Vietnamese is often racist. But Cimino gives the picture the sweep of an epic, and he does a marvelous job of rendering the bonds of community and friendship in the characters' hometown. The cast, which also includes John Cazale, George Dzundza, and a radiantly expressive Meryl Streep, is terrific. The cinematography is by Vilmos Zsigmond, and Peter Zinner provided the superb editing. Deric Washburn, working from story material by himself, Cimino, Louis Garfinkle, and Quinn K. Redeker, is credited with the screenplay.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)