Tuesday, November 29, 2016

Short Take: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1920)

Historically, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, the 1920 adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson's 1886 novella, is probably the first significant feature-length horror film produced in the United States. As for the picture itself, it is most notable for John Barrymore's flamboyant performance in the dual lead. He's all but unrecognizable underneath the Hyde make-up, but it never stunts his portrayal. He brilliantly uses the make-up to enhance the flourishes of his characterization. Barrymore's Hyde is a potent Expressionist depiction of the extremes of human malevolence: low cunning, delight in the degradation of others, and murderous violence. The misanthropic German artist George Grosz couldn't have come up with a more effective visual treatment. The stage for Barrymore is marvelously set by director John S. Robertson. The picture does a remarkable job of evoking the squalor of Victorian London; it doesn't soft-pedal the poverty, the commonplace prostitution, or the seedy opium dens. Barrymore's Hyde is a pig wallowing in the mud of a horribly ideal sty. The film also has some striking flourishes beyond Barrymore's performance, such as the dream sequence in which Hyde, personified as a gigantic spider, attacks Jekyll in his bed. Nita Naldi co-stars as the dance-hall performer whom Hyde brings low. The cinematography is by Roy F. Overbaugh. The screenplay is by Clara Beranger, and borrows elements of Thomas Russell Sullivan's stage adaptation of Stevenson's novella.

Monday, November 28, 2016

Short Take: Charade

The 1963 comedy-thriller Charade, directed by Stanley Donen, recalls the more lighthearted films of master suspense filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock. It’s not as sharp a confection as it could have been, but few films can match it for wit or glamour. An American woman in Paris (Audrey Hepburn) is suddenly widowed. Her husband has been murdered, and she finds herself a target of three of his former partners (Ned Glass, James Coburn, and George Kennedy). The men are after a fortune they and the husband helped steal, and they’re certain she’s the key to finding it. A CIA official (Walter Matthau) claims to want it back for the U. S. government, but he’s perfectly content to leave her unprotected from the trio of thugs. The wild card in the intrigue is a mysterious though charming fellow (Cary Grant), who may be working with the thugs, or a thief out for himself, or the only ally the woman has. The superbly crafted script, by Peter Stone and Marc Behm, is full of ingenious twists, surprising gags, and terrific romantic interplay between the Hepburn and Grant characters. The most refreshing aspect of the love story is that Hepburn’s character is the assertive one. Stanley Donen’s direction is somewhat uneven. The pacing is strong, the Paris locations are used well, and he brings out the glamorous charm of his two stars. But he doesn’t seem to know how to handle violence. The film is grisly when it should be discreet, and the explicitness works against the tongue-in-cheek tone. The picture quickly gets back on track after these lapses, but they may still leave one with a bad taste in one’s mouth. Yet despite the flawed moments, the picture is still one of the most entertaining Hollywood films of the early 1960s. The fine, varied score is by Henry Mancini, and Hepburn’s elegant wardrobe is courtesy of Givenchy. Charles Lang, Jr. provided the cinematography. The script is adapted from Peter Stone’s novel The Unsuspecting Wife, which was based on an earlier screenplay by Stone and Marc Behm.

Wednesday, July 13, 2016

Short Take: Mad Max: Fury Road

One could call Mad Max: Fury Road, the belated fourth film in director George Miller's action franchise, a car chase to one end of the desert and back. It would be accurate, and unpardonably flippant. This is one of the greatest of all action films. It's a marvel of kinetic staging and editing that at times seems almost abstract. In the context of a post-apocalyptic adventure thriller, Miller has achieved something close to the equivalent of Jackson Pollock's drip paintings: pure energy has been unloos'd upon the screen. The underlying story is fairly simple. The titular hero (Tom Hardy) is captured by the throngs of a desert warlord (Hugh Keays-Byrne), and finds himself in the middle of a plot involving a rebelling field marshal (Charlize Theron) and her efforts to help the warlord's unwilling harem escape. Miller's dystopian vision has intriguing details, such as the bizarre culture of the warlord's minions, and the junkyard hodgepodge of the vehicles and other machines used by the various characters. The story also has a refreshing feminist edge. The escape plot is a revolt against patriarchal oppression, and Theron's field marshal is the film's most heroic and combat-savvy character. Max proves more her capable sidekick than anything else. The pair's main allies in the second half are a band of motorcycle-riding older women, called the Vuvalini, and one sees the harem members evolve from cheesecake eye-candy to assertive heroines in their own right. Making women the heroes is an enjoyable counterpoint to the admittedly macho aesthetic of the filmmaking. The picture is terrific fun on many levels. The virtuoso team of behind-the-scenes artisans includes cinematographer John Seale, editor Margaret Sixel, and production designer Colin Gibson. Jenny Beavan did the wildly imaginative costuming. The screenplay is credited to Miller, comic-book cartoonist Brendan McCarthy, and Nico Lathouris.

Tuesday, July 12, 2016

Short Take: The Lady Eve

In The Lady Eve, writer-director Preston Sturges' wonderful 1941 romantic comedy, Henry Fonda falls for Barbara Stanwyck, and falls, and falls, and falls again. Fonda plays the shy, naïve heir to a brewery fortune. While traveling by ship to New York, he is targeted by Stanwyck's character, a cardsharp and con-artist working with her father (Charles Coburn). She effortlessly hooks and reels him in. She falls in love, too, and repeatedly thwarts her father's efforts to fleece him. But he discovers the truth about her and her father before the voyage ends, and breaks things off. Determined to get revenge, she gains entry into his family's high-society community by posing as a young British noblewoman, and again captures his heart. Sturges delivers one terrific comic set piece after another, and he's as deft at verbal humor as he is with slapstick. The two stars have never been funnier, whether it's with Fonda's pratfalls or Stanwyck's delight in her character's cynicism. But as hilarious as the picture is, the romance has weight. The best scene is when Stanwyck's character, resting her head against Fonda's, runs her fingers through his hair and beguiles him with romantic talk, all the while falling in love despite herself. One also feels the characters' pain when circumstances drive them apart. The film is one of the high points of Hollywood's Golden Age. Sturges features some delightful light humor in the picture's incidentals. The faux upper-class manner of high-society servants is satirized, most notably in casting William Demarest as the Fonda character's valet. The character is the most brusque and declassé "gentleman's gentleman" one will ever see. Sturges also gets that shy young men substitute geeky pastimes for romance. The joke comes with the book Fonda's character reads at dinner. Its title, which relates to his character's scholarly fixations, is a play on E. B. White and James Thurber's 1930s bestseller Is Sex Necessary? And Sturges has an unmatched wit when it comes to thumbing his nose at the strictures of Hollywood's Production Code. One example is the scene where editing tricks allow Stanwyck's character to relate her British noblewoman's sordid romantic past. Another is the finale, when the picture nimbly gets around the prohibition against extramarital sex being rewarded. The cast includes Eugene Pallette as the Fonda character's uncouth father, and Eric Blore, who plays Stanwyck's high-society accomplice. The screenplay is based on the Monckton Hoffe story "Two Bad Hats."

Monday, July 11, 2016

Short Take: Doctor Zhivago (1965)

Director David Lean is legendary for his attention to detail. His films often seem more realized than one might think possible. In Doctor Zhivago, he in many ways went further than he ever had before. The sets and costuming have never been more extravagantly painstaking. The shot compositions and staging have a strikingly elaborate pictorial elegance. In terms of production values and visual craftsmanship, the film is astonishing. And the drama is completely overwhelmed by the grandeur of the trappings. No movie has ever seemed so spectacular and yet so banal. One spends more than three hours watching the title character (the Keane-eyed Omar Sharif), and his experiences before, during, and after the Russian Revolution. One will be wondering what the point is long before the film ends. The center of the story is his love for the beautiful Lara (Julie Christie), but the picture is a third over before they have a scene together, and almost halfway through before they have a conversation. Their passion appears based on an infatuation borne of the time when war separated them from their spouses. But there is no feeling of rapport between the two, and no erotic tension before they begin their affair. The picture can't even find drama in adultery. Part of what goes wrong is Robert Bolt's script, which he adapted from the novel by Boris Pasternak. Bolt hasn't shaped the material into any discernible structure, and the story never seems to get started. Lean compounds the problems by not designing the scenes in terms of dramatic effect. Every moment is just a platform for the august visuals. It's a cinematic coffee-table book. Most of the cast--Sharif, Christie, Tom Courtenay (as Lara's husband), Geraldine Chaplin (who plays Zhivago's wife), and Alec Guinness (who plays his brother)--gets turned into mannequins. Rod Steiger brings some shading and tension to his role as the teenage Lara's middle-aged lover, but the performance is smothered by the production's bloat. The picture's most irritating element is Maurice Jarre's famous balalaika score. It would be fine if used with restraint, but Lean plays it incessantly. The Oscar-winning cinematography is by Freddie Francis, and the production design (which also won an Oscar) is by John Box, Terence Marsh, and Dario Simoni. A TV mini-series version, starring Hans Matheson and Keira Knightley, was released in 2002.

Saturday, July 9, 2016

The Jim Shooter "Victim" Files: Gerry Conway

This essay is adapted from a longer article that appeared at The Hooded Utilitarian on October 23, 2013.

For the introduction to "The Jim Shooter 'Victim' Files" series, click here.

Note: Gerry Conway could not be reached for comment on this article.

Gerry Conway, born in 1952, broke into comics as a scriptwriter at DC in 1968. He was 16. In 1970, after two years of writing for horror anthology titles for DC and Marvel, he took over as the regular scriptwriter for Marvel’s Daredevil series. Within a year, he had also become the regular scriptwriter for Iron Man, Sub-Mariner, and the "Inhumans" series in Amazing Adventures. In 1972, the 19-year-old Conway became Stan Lee’s successor as regular scriptwriter for The Amazing Spider-Man, the company's flagship title. While on the series, he scripted the issues featuring the deaths of Gwen Stacy and the Norman Osborn Green Goblin, as well as the story introducing the Punisher. In 1975, unhappy over the successive promotions of Len Wein and Marv Wolfman to Marvel editor-in-chief, he moved over to DC to work as an editor and scriptwriter. Conway returned to Marvel as editor-in-chief in March 1976, but stepped down less than a month later to become a writer-editor with the company. Before the end of the year, he had gone back to DC, where he worked for the next decade. In 1986, he returned to Marvel to script the launch of Spitfire and the Troubleshooters for the New Universe imprint. At the time of Shooter’s termination as editor-in-chief in April 1987, Conway was writing the Thundercats series for Marvel’s Star Comics line, as well as the New Universe title Justice.

Conway had been working regularly for Marvel for a year when Shooter was let go, so, as with Steve Englehart, knowledgeable readers would have again looked askance at Gary Groth’s inclusion of Conway in his 1987 editorial’s list of “the vast number of creators fired or otherwise driven to leave Marvel by Shooter” (TCJ #117, p. 6). As with Steve Englehart, Groth made no mention of Conway’s employment at Marvel at the time of Shooter’s firing.

Another reason readers might have looked askance was because when Conway left Marvel in 1976, the editor-in-chief was his immediate successor, Archie Goodwin. Shooter was still the company’s associate editor at the time. And Conway didn’t report to either Goodwin or Shooter. The writer-editor contract specified that he reported directly to Marvel publisher Stan Lee.

There was no correction printed with regard to that editorial, and in the 1994 “Our Nixon” essay, Groth also included Conway in the specific list of people whom Groth stated that “under Shooter Marvel lost […] often because of an unresolvable dispute between the creator and Shooter”, and who “occasionally went on the record stating his unequivocal disdain for Shooter’s ethics and professionalism” (TCJ #174, p.18). Groth again made no mention that when Shooter left Marvel, Conway was regularly working for the company.

As he did with Steve Englehart, Groth misleadingly extended the Marvel-under-Shooter description to mean when Shooter was associate editor as well as editor-in-chief. As for the basis for Conway’s inclusion, it appears to be the following statement from the 1981 feature-length interview with Conway in The Comics Journal #69.

Even if one takes this at face value, it does not support Groth's claim that Conway "was fired or otherwise driven to leave Marvel by Shooter." Although Conway does not specify his reasons for his decision to leave Marvel, it's clear that problems with Shooter weren't among them. As he said, "When I worked there as a writer-editor, I really didn’t have anything to do with Jim." All Conway is alleging is that, after he announced his departure, Shooter took steps that hastened that exit. It's far from the same thing. Groth again appears to be playing fast and loose with what allegedly happened.

Getting back to Conway, there is nothing indicating his account of Shooter’s conduct is anything but speculation, and reckless speculation at that. How did Conway know what Shooter said or didn't say to Lee? And isn't Lee responsible for his own actions? He'd been a publishing professional for over 35 years at this point. It's hard to imagine him being influenced in this way by a junior staffer.

If I had to guess what’s going on here, I would say that Conway was looking to absolve Lee of responsibility for Lee's treatment of him. Further, he was looking to blame another person--here, Shooter--for Lee’s actions, and then treat that person, not Lee, as the enemy.

This appears to be a pattern of behavior on Conway’s part. When Conway was passed over for the editor-in-chief position in favor of Len Wein in 1974, and again passed over for it in 1975 when Marv Wolfman replaced Wein, he has said it “cluttered up my relationship with Marv and Len, when they were put in over me” (TCJ #69, p. 72). The implication of this was that he blamed them for Lee’s decision to hire them, rather than Lee himself. In a 2011 blog post (click here), Shooter says Conway told him that “Marv and Len had lobbied against his being hired and prevailed.” Shooter also told Sean Howe that Conway said he intended to drive Len Wein to quit because “[t]he bastard screwed me, and I want rid of him." [emphasis in the original] (Untold Story, p. 184). As can be seen, there’s first the shifting of responsibility away from Lee, and then the demonization of the person blamed instead.

Roy Thomas, who was perhaps Conway’s closest friend in the comics field, as well as the Marvel veteran who knew Lee best, said in 1980 that he considered Lee specifically responsible for what happened to Conway.

It appears Lee, at least in practice, had a policy when it came to the scriptwriters who had served as editor-in-chief and, upon stepping down, were granted writer-editor contracts. If they quit to work for DC, Lee did not want them working for Marvel from that moment forward. The first person to be confronted with this was Len Wein. In 1977, Wein left Marvel for DC. According to Kim Thompson, in a news report he wrote for The Comics Journal, Wein told him “Lee angrily assured him [Wein] that he would never work for the company again” (TCJ #56, p. 12). When Marv Wolfman announced he was leaving Marvel for DC in 1979, Lee ordered that Wolfman’s outstanding contractual assignments be rescinded, and that Wolfman was to receive his remaining vacation and sick pay instead of the salary he would have been due for that work (TCJ #52, p. 8). Conway appears to have been treated the same as Wein and Wolfman, and for the the same reason.

Beyond that, it’s my view that Stan Lee had plenty of reason to be angry over Conway’s decision to leave for DC. Conway was hired for the editor-in-chief position after lobbying for it through Roy Thomas, who then recommended Conway for the job (Untold Story, p.183). Lee took a sizable chance on hiring a largely untested 23-year-old, and Conway essentially threw the opportunity back in Lee's face: he resigned from the job after less than a month. He then immediately played on Lee's goodwill again and negotiated an astonishingly expansive writer-editor contract. It required Marvel to give him eight ongoing scriptwriting assignments, twice as much as that of any other writer at the company. Now, five of those assignments weren’t a problem. Conway took over two titles that were left open by Englehart's departure, one from Tony Isabella’s, one that Archie Goodwin left when Goodwin succeeded Conway as editor-in-chief, and one that Marv Wolfman had vacated to take over another series. However, Steve Gerber, one of the company’s most valued scriptwriters, had to be removed from one of his books to accommodate Conway, and the company also had to launch two new titles to fill out the balance of Conway’s quota. The contract was for three years. After Lee had gone to these lengths on Conway’s behalf, including potentially alienating Gerber, Conway threw it all back in Lee’s face again. He decided after about six months to break the contract and return to DC. If I had been Stan Lee, I probably would have been scooting Conway out the door as quickly as I could, too.

I also note that Shooter has stated he did not have a positive working relationship with Lee until the two began collaborating on the writing of the Spider-Man newspaper strip (click here). This would have been in 1977, after Conway left the company. If what Shooter says is accurate, he did not seem to have "Stan's ear" at the time.

Conway observes that, after he left, Shooter took over some of his scriptwriting assignments. That's correct, as did Goodwin, Roger Slifer, David Anthony Kraft, Bill Mantlo, and Chris Claremont. Goodwin was the editor-in-chief, Slifer and Kraft were both editorial staffers, Mantlo was possibly still on staff at this time, and Claremont was known to regularly hang out in the Marvel offices. Pardon my sarcasm, but perhaps it wasn’t just Shooter who might have influenced Lee to give Conway the early boot. It could have been a conspiracy the entire office was in on.

Now let’s discuss the money that Shooter’s alleged influencing of Lee cost Conway.

In the 1981 quote, Conway describes this as “an advance loan” for assigned work. Conway was actually benefitting from a secret, massive (and benevolently intended) pre-payment accounting scam being run by Marvel production manager John Verpoorten. (Sean Howe describes the scam on page 201 of Marvel Comics: The Untold Story.) According to Shooter (click here), when Conway went over to DC, he informed them that he owed Marvel the money. DC cut Marvel a check for the amount and arranged an internal payment plan with Conway to cover the balance. If this is accurate, Conway just ended up repaying the money in a different manner than he intended. If he lost money, it was because he wasn’t able to repay the money by working for Marvel and DC simultaneously, and there's no indication that Marvel would have ever allowed him to do that.

What Shooter says happened next doesn’t really reflect on Conway, but I’d like to include it, just to give an idea of how disorganized things were at Marvel at the time:

Gerry Conway continued to work for Marvel after Shooter’s departure. His efforts included extended runs as scriptwriter for Spectacular Spider-Man, Web of Spider-Man, and Conan the Barbarian. He also did occasional work for DC during this time. He left the field in the early 1990s to work as a writer and producer in series television. His most notable TV credit is the rerun perennial Law & Order: Criminal Intent, which he worked on as a producer for four seasons. He wrote or co-wrote 12 episodes. He returned to work for DC in 2009 and 2010, and did some new scriptwriting for Marvel in 2015.

Related posts:

-- Tony Isabella

-- Steve Englehart

-- Mary Skrenes

-- Len Wein

For the introduction to "The Jim Shooter 'Victim' Files" series, click here.

Note: Gerry Conway could not be reached for comment on this article.

Gerry Conway, born in 1952, broke into comics as a scriptwriter at DC in 1968. He was 16. In 1970, after two years of writing for horror anthology titles for DC and Marvel, he took over as the regular scriptwriter for Marvel’s Daredevil series. Within a year, he had also become the regular scriptwriter for Iron Man, Sub-Mariner, and the "Inhumans" series in Amazing Adventures. In 1972, the 19-year-old Conway became Stan Lee’s successor as regular scriptwriter for The Amazing Spider-Man, the company's flagship title. While on the series, he scripted the issues featuring the deaths of Gwen Stacy and the Norman Osborn Green Goblin, as well as the story introducing the Punisher. In 1975, unhappy over the successive promotions of Len Wein and Marv Wolfman to Marvel editor-in-chief, he moved over to DC to work as an editor and scriptwriter. Conway returned to Marvel as editor-in-chief in March 1976, but stepped down less than a month later to become a writer-editor with the company. Before the end of the year, he had gone back to DC, where he worked for the next decade. In 1986, he returned to Marvel to script the launch of Spitfire and the Troubleshooters for the New Universe imprint. At the time of Shooter’s termination as editor-in-chief in April 1987, Conway was writing the Thundercats series for Marvel’s Star Comics line, as well as the New Universe title Justice.

Conway had been working regularly for Marvel for a year when Shooter was let go, so, as with Steve Englehart, knowledgeable readers would have again looked askance at Gary Groth’s inclusion of Conway in his 1987 editorial’s list of “the vast number of creators fired or otherwise driven to leave Marvel by Shooter” (TCJ #117, p. 6). As with Steve Englehart, Groth made no mention of Conway’s employment at Marvel at the time of Shooter’s firing.

Another reason readers might have looked askance was because when Conway left Marvel in 1976, the editor-in-chief was his immediate successor, Archie Goodwin. Shooter was still the company’s associate editor at the time. And Conway didn’t report to either Goodwin or Shooter. The writer-editor contract specified that he reported directly to Marvel publisher Stan Lee.

There was no correction printed with regard to that editorial, and in the 1994 “Our Nixon” essay, Groth also included Conway in the specific list of people whom Groth stated that “under Shooter Marvel lost […] often because of an unresolvable dispute between the creator and Shooter”, and who “occasionally went on the record stating his unequivocal disdain for Shooter’s ethics and professionalism” (TCJ #174, p.18). Groth again made no mention that when Shooter left Marvel, Conway was regularly working for the company.

As he did with Steve Englehart, Groth misleadingly extended the Marvel-under-Shooter description to mean when Shooter was associate editor as well as editor-in-chief. As for the basis for Conway’s inclusion, it appears to be the following statement from the 1981 feature-length interview with Conway in The Comics Journal #69.

Jim [Shooter] was my assistant at Marvel for about a month, and that’s really been the extent of our relationship. When I worked there as a writer-editor, I really didn’t have anything to do with Jim. When I left, however, Archie Goodwin was on vacation during the week that I left Marvel. It wasn’t my intention to make a sudden break, one day I’d be working for Marvel, the next day I wouldn’t. It was my intention to give them the option of letting me segue out over a period of a month, to complete the work that I’d already been assigned and paid for on the basis of an advance loan. But Jim, who was Archie’s assistant and the person in charge of the office at the time, had Stan’s ear and said to Stan, “Well, gee, Stan, do we really want to have a writer who’s already decided to leave us working for us over the next few weeks possibly turning out work on an inferior level because he’s so disinterested? Let’s get that work away from him.” That cost me almost $4000. […] Now I wouldn’t want to say Jim did that out of maliciousness or a feeling of ambition, but I do know that several of the stories that were taken away from me were later written by Jim. (TCJ #69, p. 82)

Even if one takes this at face value, it does not support Groth's claim that Conway "was fired or otherwise driven to leave Marvel by Shooter." Although Conway does not specify his reasons for his decision to leave Marvel, it's clear that problems with Shooter weren't among them. As he said, "When I worked there as a writer-editor, I really didn’t have anything to do with Jim." All Conway is alleging is that, after he announced his departure, Shooter took steps that hastened that exit. It's far from the same thing. Groth again appears to be playing fast and loose with what allegedly happened.

Getting back to Conway, there is nothing indicating his account of Shooter’s conduct is anything but speculation, and reckless speculation at that. How did Conway know what Shooter said or didn't say to Lee? And isn't Lee responsible for his own actions? He'd been a publishing professional for over 35 years at this point. It's hard to imagine him being influenced in this way by a junior staffer.

If I had to guess what’s going on here, I would say that Conway was looking to absolve Lee of responsibility for Lee's treatment of him. Further, he was looking to blame another person--here, Shooter--for Lee’s actions, and then treat that person, not Lee, as the enemy.

This appears to be a pattern of behavior on Conway’s part. When Conway was passed over for the editor-in-chief position in favor of Len Wein in 1974, and again passed over for it in 1975 when Marv Wolfman replaced Wein, he has said it “cluttered up my relationship with Marv and Len, when they were put in over me” (TCJ #69, p. 72). The implication of this was that he blamed them for Lee’s decision to hire them, rather than Lee himself. In a 2011 blog post (click here), Shooter says Conway told him that “Marv and Len had lobbied against his being hired and prevailed.” Shooter also told Sean Howe that Conway said he intended to drive Len Wein to quit because “[t]he bastard screwed me, and I want rid of him." [emphasis in the original] (Untold Story, p. 184). As can be seen, there’s first the shifting of responsibility away from Lee, and then the demonization of the person blamed instead.

Roy Thomas, who was perhaps Conway’s closest friend in the comics field, as well as the Marvel veteran who knew Lee best, said in 1980 that he considered Lee specifically responsible for what happened to Conway.

Marvel has had a tendency in recent years to be very vindictive toward people who leave it to work for the competition. They go far beyond any kind of professional reaction. Stan generally has reasonably good and humane instincts, but once in a while he’ll just decide that if somebody does something, he’s never going to work for Marvel again. He did this with Len, and with Gerry […] (TCJ #61, p. 85)

It appears Lee, at least in practice, had a policy when it came to the scriptwriters who had served as editor-in-chief and, upon stepping down, were granted writer-editor contracts. If they quit to work for DC, Lee did not want them working for Marvel from that moment forward. The first person to be confronted with this was Len Wein. In 1977, Wein left Marvel for DC. According to Kim Thompson, in a news report he wrote for The Comics Journal, Wein told him “Lee angrily assured him [Wein] that he would never work for the company again” (TCJ #56, p. 12). When Marv Wolfman announced he was leaving Marvel for DC in 1979, Lee ordered that Wolfman’s outstanding contractual assignments be rescinded, and that Wolfman was to receive his remaining vacation and sick pay instead of the salary he would have been due for that work (TCJ #52, p. 8). Conway appears to have been treated the same as Wein and Wolfman, and for the the same reason.

Beyond that, it’s my view that Stan Lee had plenty of reason to be angry over Conway’s decision to leave for DC. Conway was hired for the editor-in-chief position after lobbying for it through Roy Thomas, who then recommended Conway for the job (Untold Story, p.183). Lee took a sizable chance on hiring a largely untested 23-year-old, and Conway essentially threw the opportunity back in Lee's face: he resigned from the job after less than a month. He then immediately played on Lee's goodwill again and negotiated an astonishingly expansive writer-editor contract. It required Marvel to give him eight ongoing scriptwriting assignments, twice as much as that of any other writer at the company. Now, five of those assignments weren’t a problem. Conway took over two titles that were left open by Englehart's departure, one from Tony Isabella’s, one that Archie Goodwin left when Goodwin succeeded Conway as editor-in-chief, and one that Marv Wolfman had vacated to take over another series. However, Steve Gerber, one of the company’s most valued scriptwriters, had to be removed from one of his books to accommodate Conway, and the company also had to launch two new titles to fill out the balance of Conway’s quota. The contract was for three years. After Lee had gone to these lengths on Conway’s behalf, including potentially alienating Gerber, Conway threw it all back in Lee’s face again. He decided after about six months to break the contract and return to DC. If I had been Stan Lee, I probably would have been scooting Conway out the door as quickly as I could, too.

I also note that Shooter has stated he did not have a positive working relationship with Lee until the two began collaborating on the writing of the Spider-Man newspaper strip (click here). This would have been in 1977, after Conway left the company. If what Shooter says is accurate, he did not seem to have "Stan's ear" at the time.

Conway observes that, after he left, Shooter took over some of his scriptwriting assignments. That's correct, as did Goodwin, Roger Slifer, David Anthony Kraft, Bill Mantlo, and Chris Claremont. Goodwin was the editor-in-chief, Slifer and Kraft were both editorial staffers, Mantlo was possibly still on staff at this time, and Claremont was known to regularly hang out in the Marvel offices. Pardon my sarcasm, but perhaps it wasn’t just Shooter who might have influenced Lee to give Conway the early boot. It could have been a conspiracy the entire office was in on.

Now let’s discuss the money that Shooter’s alleged influencing of Lee cost Conway.

In the 1981 quote, Conway describes this as “an advance loan” for assigned work. Conway was actually benefitting from a secret, massive (and benevolently intended) pre-payment accounting scam being run by Marvel production manager John Verpoorten. (Sean Howe describes the scam on page 201 of Marvel Comics: The Untold Story.) According to Shooter (click here), when Conway went over to DC, he informed them that he owed Marvel the money. DC cut Marvel a check for the amount and arranged an internal payment plan with Conway to cover the balance. If this is accurate, Conway just ended up repaying the money in a different manner than he intended. If he lost money, it was because he wasn’t able to repay the money by working for Marvel and DC simultaneously, and there's no indication that Marvel would have ever allowed him to do that.

What Shooter says happened next doesn’t really reflect on Conway, but I’d like to include it, just to give an idea of how disorganized things were at Marvel at the time:

DC’s check was delivered to Marvel’s accounting department. [Marvel's chief financial officer] Barry Kaplan had no clue, at that point (before the scam came to light) what it was for, assumed it was a mistake and sent it back! DC then sent the check to John Verpoorten, probably at Gerry’s suggestion. The five figure [sic] check was found in Verpoorten’s drawer after he died.

Gerry Conway continued to work for Marvel after Shooter’s departure. His efforts included extended runs as scriptwriter for Spectacular Spider-Man, Web of Spider-Man, and Conan the Barbarian. He also did occasional work for DC during this time. He left the field in the early 1990s to work as a writer and producer in series television. His most notable TV credit is the rerun perennial Law & Order: Criminal Intent, which he worked on as a producer for four seasons. He wrote or co-wrote 12 episodes. He returned to work for DC in 2009 and 2010, and did some new scriptwriting for Marvel in 2015.

Related posts:

- The Jim Shooter "Victim" Files

-- Tony Isabella

-- Steve Englehart

-- Mary Skrenes

-- Len Wein

Friday, July 8, 2016

Short Take: I Walked with a Zombie

Producer Val Lewton's I Walked with a Zombie (1943) is nowhere as cheesy as it sounds. Despite the title, it's far more eerie than scary. The zombie of the title isn't even a monster. She's the young wife (Christine Holland) of a sugar plantation owner (Tom Conway) in the West Indies. A tropical disease has reduced her to a semi-vegetative state; she can walk, but her higher brain functions are otherwise gone. The plantation owner hires a nurse (Frances Dee) to care for her, and the nurse becomes intrigued with the possibility of the island's slave descendants being able to cure the wife through voodoo. The nurse's interest in the voodoo culture indirectly leads to the sordid dramas of the plantation owner, his brother (James Ellison), and their mother (Edith Barrett) being brought into the open. Director Jacques Tourneur and cinematographer J. Roy Hunt deliver gorgeously atmospheric visuals, and the film is beautifully paced. But the portrayal of voodoo and the slave descendants is quite objectionable. The picture uses voodoo to tease the viewer with the prospect of the uncanny. It's imaginatively handled in terms of storytelling technique, but it's also exploitive and racist. The slave descendants are portrayed as primitive others, and the voodoo religion is reduced to an exotic means of spicing up the proceedings. With its artful form and offensive content, the film combines some of the best and worst aspects of pulp material. The screenplay is credited to Curt Siodmak and Ardel Wray. The official source material is a non-fiction article by Inez Wallace, but there are echoes throughout of Charlotte Brontë's great 1847 novel Jane Eyre.

Thursday, July 7, 2016

Short Take: Swing Time

The major difference between 1935's Top Hat, the greatest of the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers vehicles, and the following year's Swing Time, is that while Top Hat seeks to delight, Swing Time's goal seems mainly to impress. The picture has no magic. Only "Pick Yourself Up," the first of the stars' three dances, has a sense of joy from start to finish. "Waltz in Swing Time" and "Never Gonna Dance," the couple's other two numbers, start beautifully. But then the choreography seems more concerned with razzle-dazzle than expression. By the end of the dances, one is certainly astonished by the skill and (especially) the speed with which Astaire and Rogers perform the complex routines, but there's no emotional sweep to carry one along. It's empty virtuosity. Astaire's showpiece solo number, "Bojangles in Harlem," is also more impressive than likable, although for different reasons. There are two sections. The first has Astaire performing with two dozen chorus girls, and the second has him dancing with three oversize cast shadows of himself. On a technical level, it may be the most spectacular tap-dance sequence ever filmed. Unfortunately, Astaire performs it in blackface. While the racism is more insensitive than patronizing, and it's not at all hate-driven, it still doesn't sit well. The film has other major weaknesses. The first is that the screenplay, credited to Howard Lindsay and Allan Scott, doesn't have the snap of well crafted romantic comedy. The scenes never seem to be going anywhere. A bigger problem is the overly stately direction by George Stevens. His staging and shot compositions are too studied, and he gives the film's story sections a leaden pace. It feels like an eternity between dance numbers. Even Van Nest Polglase's Art Deco sets seem drained of panache. The cast also includes Victor Moore and Helen Broderick, who play the stars' respective sidekicks. The songs are by Jerome Kern (music) and Dorothy Fields (lyrics). Fred Astaire choreographed the numbers with Hermes Pan.

Reviews of other Astaire & Rogers films:

Wednesday, July 6, 2016

Short Take: Ghostbusters (1984)

Ghostbusters (1984) is one of the two or three most successful comedy films ever produced, but one may find it a letdown. It's more silly than funny, and the cheesy adventure plot may leave one feeling it's strictly for kids. It has a straightforward premise: After three parapsychologists (Bill Murray, Dan Aykroyd, and Harold Ramis) lose their university research grant, they set up a pest-control business specializing in ghosts and other supernatural phenomena. There are enjoyable things in the picture. The heroes' first job, in which they trap a ghost that's menacing a luxury hotel, is a good slapstick set piece. Sigourney Weaver, who plays a cellist whose apartment is haunted, turns in a fine comic performance. She's drily amusing in her early scenes, in which she's constantly fending off unwanted male attention, and she's deliriously funny in her later ones, after the character has been possessed by an ancient demon. Some incidental bits, such as Ray Parker, Jr.'s witty jingle-style theme song, have their charm. But the comic aspects of the script, by Aykroyd and Ramis, are poorly developed. Most of the one-liners feel like throwaways. Potentially funny ideas, such as a 100-foot marshmallow mascot stalking the heroes on Central Park West, aren't shaped into gags. They're just dumped into the proceedings as if the absurdity by itself was hilarious. Several talented performers--Rick Moranis as a nerdy accountant, Annie Potts as the heroes' jaded secretary, William Atherton as a quick-tempered EPA investigator--feel stranded. (Moranis has one good line. During a party scene, the accountant hears a gargoyle roar in the next room, and he asks who brought the dog.) Yet for all one's reservations, it must be acknowledged that many adore the picture. Its box-office success and iconic pop-culture status attest to that. Opinions tend to hinge on how one responds to Bill Murray. If you feel the picture is a strong showcase for his slobby wiseguy persona, you'll love it. If you're indifferent to his presence here, the picture leaves you cold. Ivan Reitman directed.

Tuesday, July 5, 2016

Short Take: Bizet's Carmen

With Bizet's Carmen, the Italian director Francesco Rosi has put together what is perhaps the definitive film version of Georges Bizet's 1875 opera. The story is fairly homely. Don José, a dutiful career soldier, seems to have his whole life ahead of him. He's respected by his superiors, and he's about to become engaged. Micaëla, his prospective fiancée, is a loyal, responsible woman who has loved him her whole life. But when he meets Carmen, a flirtatious, headstrong factory worker, he's smitten, and he throws it all away for her. Her love proves fleeting, though, and her affections shift to Escamillo, a charismatic toreador. The libretto may seem banal, but Bizet's joyous sense of melody and orchestration made the opera one of the most popular ever written. Rosi's treatment is spectacular. He shot the film on location in Andalusia, and the open-air settings provide a grand stage. He also assembled a first-rate cast. Plácido Domingo, arguably the world's greatest tenor, stars as Don José. Carmen and Micaëla are respectively played by Julia-Migenes Johnson and Faith Esham, two seasoned American sopranos. The celebrated Italian basso Ruggero Raimondi plays Escamillo. It's a wonderful production, and it has its surprises. Domingo and Raimondi are the big-name draws in the cast, but it's the women who dominate the film. Julia Migenes-Johnson is terrific in the title role. She plays Carmen's brazen, taunting sexuality with a hilarious comic edge, and that joy in naughtiness walks hand-in-hand with a fierce willfulness. Her Carmen is a tiny woman, but she takes what she wants, and God help anyone who gets in her way. Her showpiece number, the first act's famous "Habañera," is a saucy delight. And while Migenes-Johnson takes acting honors, Faith Esham is the stand-out in terms of singing. Her third-act solo "Je dis que rien ne m'epouvante [I say nothing frightens me]," has the film's most gorgeously performed vocals. Rosi seems to know it, too. He gives the recording a witty encore: the song repeats as if it was an extended echo through the mountains. The awesome landscape visuals not only enhance the beauty of Esham's singing, they complete it. For all the song's intimacy, it may be the most epic musical moment ever filmed. The picture's behind-the-scenes artisans--including cinematographer Pasqualino de Santis, production designer Enrico Job, and choreographer Antonio Jades--all do superb work. The score was performed by the Orchestre National de France, and conducted by Lorin Maazel. Rosi and Tonino Guerra adapted Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy's 1875 libretto, which was in turn adapted from a 1845 novella by Prosper Merimée.

Monday, July 4, 2016

Short Take: Don't Look Now

Director Nicolas Roeg's 1973 horror thriller Don't Look Now is a small masterpiece of atmosphere and portent. Some time after their young daughter accidentally drowns, an England-based couple (Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland) travel to Venice, where the husband is overseeing the restoration of a centuries-old church. He has put the tragedy behind him, but she is still grieving. They meet two elderly sisters (Hilary Mason and Clelia Matania) at a restaurant, and one claims to have psychic powers. The woman tells the wife the spirit of the daughter is still with her and her husband. The woman also says the husband is in danger if he remains in Venice. The husband scoffs, but things happen that make him wonder. Is the spirit of their daughter with them? Is he in danger? Is his wife, with her grief and her embrace of the old woman's claims, at risk herself? And can he perhaps see hints of the future, too? Nicolas Roeg binds the story together with a series of ominous visual motifs. Some go nowhere, and others go to unexpected places, but all of them infuse the proceedings with a palpable sense of dread. Roeg and cinematographer Anthony B. Richmond enhance the creepiness with their strikingly moody depiction of Venice in autumn. The gray skies, brackish-looking canal waters, and decrepit building façades cast a pall of decay. The editing, credited to Graeme Clifford, is also remarkable. It is beautifully lyrical at times, such as when the couple's pre-dinner lovemaking is intercut with their dressing to go out afterward. But the expertly timed use of flashbacks, flash-forwards, and repetition of motifs also create chillingly eerie rhythms. The screenplay, credited to Allan Scott and Chris Bryant, from a Daphne du Maurier short story, doesn't add up to much. One can feel the inventiveness draining out of it in the film's second half. The climactic scene, where the husband confronts what he believes is the ghost of his daughter, is a groaner. One may feel it doesn't matter, though. The artful kitsch-modernist surface keeps things quite compelling. Pino Donaggio provided the film's score.

Saturday, July 2, 2016

Friday, July 1, 2016

Short Take: The Curse of the Cat People

Producer Val Lewton's Cat People was an enormous box-office success upon its release in 1942. His 1944 The Curse of the Cat People is ostensibly a sequel, but it is quite far removed from the subject of its predecessor. While it references the earlier film, and the cast returns to play the same characters, it seems to have been conceived as a stand-alone project. The connections to the earlier film are all but nominal. There's certainly nothing about the passions of love turning women into homicidal panthers. It's instead a story about a lonely little girl (Ann Carter) with a wayward imagination. Her flights of fancy concern her parents (Kent Smith and Jane Randolph, both from the earlier film), and the father attempts to police her behavior. But he only succeeds in making the girl retreat further inward. The two new friends she makes only complicate things. The first is the ghost of the father's first wife (Simone Simon, also from the earlier film). The second is an elderly actress (Julia Deen) who shares a house with a resentful, live-in adult daughter (Elizabeth Russell). DeWitt Bodean's screenplay is poorly developed. The girl's friendships with the ghost and the actress only illustrate the pathos of the girl's circumstances. These relationships don't intersect until the contrived, melodramatic finale, and they don't add any depth to the material. The film does a capable job of hitting obvious sentimental notes, but that's the most that can be said for it. Lewton, directors Gunther von Fritsch and Robert Wise, and the superb cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca otherwise treat the film as a platform for Gothic visuals, which are far more decorative than poetic. The cast also includes Eve March as the girl's kindergarten teacher, and Sir Lancelot as the parents' housekeeper.

Thursday, June 30, 2016

Short Take: Cat People (1942)

Cat People may be the most artful horror/monster picture of Hollywood's Golden Age. Simone Simon plays a fashion illustrator who has recently come to New York from Serbia. She meets and falls in love with a boating engineer (Kent Smith), and the two are married shortly thereafter. But she refuses to consummate the marriage or even kiss him. She believes she is a descendant of a mountain tribe that embraced the occult, and who become panthers while in the grip of desire, jealousy, or even anger at an unwanted pass. Her husband, believing this a superstition borne of insecurity, tolerates her reticence for a time. But he ultimately demands she see a psychiatrist (Tom Conway), and she begins to feel her marriage is challenged from all sides: her upset at disappointing her husband; her suspicion of his relationship with a co-worker (Jane Randolph); and her having to contend with the psychiatrist, who may be taking an unprofessional interest in her. Mysterious events ensue, and with them the question of whether her beliefs aren't superstition. Producer Val Lewton and director Jacques Tourneur couldn't afford the special effects and other production trappings of King Kong and the Universal Studios monster features, but they more than compensated with an extraordinarily sophisticated use of horror and suspense tropes. Most of the film's thrills are built around ambiguity and portent, and the restraint makes the overt violence, when it finally comes, stunningly effective. The film's power owes far more to imagination than blatancy, and it's exhilarating. The screenplay is credited to DeWitt Bodean, and is based on Lewton's 1930 short story "The Bagheeta." Nicholas Musuraca provided the beautifully composed black-and-white cinematography. A remake of the film, directed by Paul Schrader, was released in 1982.

Wednesday, June 29, 2016

Short Take: Blue Velvet

Blue Velvet (1986) is part small-town crime thriller and part coming-of-age story, all shaped by the unique vision of writer-director David Lynch. A college student (Kyle MacLachlan) returns to his North Carolina hometown after his father suffers a stroke. Walking through a field on his way home from the hospital, he discovers a rotting human ear. After turning it over to the police, a detective's teenage daughter (Laura Dern) tells him there may be a connection between the ear and a local bar singer (Isabella Rossellini). With the daughter's help, the young man plots to covertly search the singer's apartment. Once inside, he discovers more than he ever wanted to know--about the singer, his hometown, and the darkest sides of his own personality. Lynch has a remarkable imagination: unbridled conceptually, but strikingly disciplined in terms of execution. One can tell one is in the hands of a great filmmaker right from the first frames, where the brightly idyllic images of small-town life give way to the brutal interactions of insects beneath the perfectly cultivated lawns. It's a brilliantly succinct allegory for the film's main theme: the ugliness found beneath genteel surfaces. Lynch builds the drama around the taboos of voyeurism, fetishism, and sadomasochistic desire, and he makes the story's key scenes, while only mildly violent in surface terms, among the most shocking ever filmed. He also gives free rein to whimsy, and the trippy moments range from oddball humor to reaches into the uncanny. The most brilliant is a hallucinatory set piece in which an effete thug (Dean Stockwell) mimes a performance of Roy Orbison's "In Dreams." But Lynch's wild card is his villain: a local crime boss played with ferocious intensity by Dennis Hopper. The character is the personification of depravity--the human analogue of the brutal insects hiding in the grass, and the symbol of the dark impulses the young hero fears within himself. It's a tribute to both Lynch and Hopper that the crime boss carries this allegorical freight while being nothing less than terrifying. Lynch's other collaborators, including the rest of the cast and the behind-the-scenes artisans, are remarkable as well. The most noteworthy are Frederick Elmes, who provided the gorgeous cinematography, and Alan Splet, who was responsible for the eerily detailed sound design. The film's score, which ranges from jazz to lush strings to romantic synthesizer pop, is by Angelo Badalamenti.

Tuesday, June 28, 2016

Short Take: The Lady Vanishes

On the surface, The Lady Vanishes (1938) is one of the conspiracy thrillers director Alfred Hitchcock is famous for. A young British woman (Margaret Lockwood) befriends an elderly governess (Dame May Whitty) while riding on a cross-continental train. After the younger woman awakens from a nap, she finds the governess has disappeared, and no one on the train has any recollection of her. Was the older woman kidnapped, and are the other passengers part of a conspiracy to cover it up? Or is the younger woman hallucinating from a concussion suffered before she boarded the train? Most Hitchcock thrillers have a sense of humor about their teasing suspense tropes. But this picture goes far beyond wry self-awareness. Its tongue is as firmly in cheek as a Mad magazine parody. It's not an immersive piece of storytelling; one either enjoys it for the mocking treatment of the story conventions, or one doesn't. Hitchcock's direction is marvelous. The staging is remarkably sophisticated, and the expert pacing keeps the movie hurtling forward. His filmmaking virtuosity is thrilling in its own right. The script, credited to Sidney Gilliat and Frank Launder, is erratic. It does a witty job of sustaining the genre satire once it gets going, but it is hobbled by a largely extraneous first act, and the jokes, while amusing, aren't especially memorable. The cast also includes Michael Redgrave as the leading man who is not a love interest, Paul Lukas as the sinister psychiatrist, and the comedy duo of Naunton Wayne and Basil Radford as Caldicott and Childers, the cricket enthusiasts who are also passengers on the train. The source novel is The Wheel Spins, by Ethel Lina White. The film is the last one from Hitchcock's British period. After it was released, he moved to the United States and began making films through the Hollywood studios.

Monday, June 27, 2016

Short Take: The Gay Divorcee

The Gay Divorcee (1934) was the first starring vehicle for Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. (They first appeared together as supporting players in 1933’s Flying Down to Rio.) But the film clearly wasn’t put together as a showcase for the duo’s magic on the dance floor. It’s just a musical in which they happen to play the leads. They don’t dance together until the “Night and Day” scene, which doesn’t come until midway through. It is a bit of a letdown besides. The dancing is beautiful, but it doesn’t start until the number is half over, and it doesn’t do much to enhance the scene’s drama. One doesn’t feel, as in Top Hat’s “Isn’t This a Lovely Day (to Be Caught in the Rain),” that he’s winning her heart through the dance. Instead, she goes immediately from trying to get away from him to the full swoon of being in love. The dance is all climax and no build-up. Astaire and Rogers are also rather incidental to the film’s showpiece production number, the 17-minute “The Continental.” They take center stage at a couple of points, but the scene belongs to director Mark Sandrich and ensemble choreographer Dave Gould. It tries to outdo the kaleidoscopic spectacle of Busby Berkeley’s dance set pieces, and it’s a pretty fair attempt. The stars’ best moment is the film’s closing scene, where they dance across the furniture while making their way out the door. The film has one other notable scene, although it doesn’t feature Astaire or Rogers. It’s the amusing “Let’s K-nock K-nees” number, performed by Betty Grable, Edward Everett Horton, and the film’s chorus. The rest of the picture is a trite mistaken-identity romantic farce. The cast also includes Alice Brady, Eric Blore, and, as the odiously caricatured Italian, Erik Rhodes. The script, credited to George Marion, Jr., Dorothy Yost, and Edward Kaufman, is based on the play Gay Divorce, by Dwight Taylor.

Reviews of other Astaire & Rogers films:

Reviews of other Astaire & Rogers films:

Saturday, June 25, 2016

The Jim Shooter "Victim" Files: Steve Englehart

This essay is adapted from a longer article that appeared at The Hooded Utilitarian on October 23, 2013.

For the introduction to "The Jim Shooter 'Victim' Files" series, click here.

Born in 1947, Steve Englehart broke into the comics business in late 1970. He graduated with a bachelor's degree in psychology from Wesleyan University in 1969. He also served for a time in the U. S. Army. He started as a freelance artist for various publishers, but quickly shifted to scriptwriting. Long runs on Marvel’s Captain America and The Avengers made him one of the field's most admired scriptwriters before he left for DC in 1976.

Before getting into the specific circumstances of Englehart’s departure from Marvel, I would like to discuss at length how Englehart’s situation has been exploited to attack Jim Shooter. It’s a good study in the tactics Gary Groth and Sean Howe, Shooter’s most conspicuous detractors, have used in efforts to defame him.

Given the prominent role Groth and The Comics Journal have in shaping perceptions of comics history, his portrayal of Shooter's dealings with various comics personnel will be discussed in each instance. For the same reason, Sean Howe's treatments in Marvel Comics: The Untold Story will be examined as well.

In Groth’s 1987 editorial about Jim Shooter’s termination as Marvel editor-in-chief, he included Englehart in a list of “the vast number of creators fired or otherwise driven to leave Marvel by Shooter” (TCJ #117, p. 6). This reference should have struck a discordant note with any knowledgeable reader.

The most immediate reason was that, at the time of Shooter’s firing in April 1987, Englehart was working for Marvel. He was the regular scriptwriter on three ongoing company-owned titles: Fantastic Four, Silver Surfer, and West Coast Avengers. He had been writing at least two titles a month for the company’s various imprints for the previous two years. He began regularly publishing new work through Marvel again in February of 1983, when the first issue of his creator-owned series Coyote shipped to retailers.

Beyond that, it was well known in comics circles that Englehart quit Marvel in 1976 because of conflicts with Gerry Conway, who was then the company’s editor-in-chief. One reason it was known was an interview with Englehart in The Comics Journal #63 that Groth helped conduct. Englehart discussed his problems with Conway at length. His statements gained additional notoriety when Conway responded with a letter, published in The Comics Journal #68, that may well be the single most intemperate, vituperative, and outright nasty piece of writing the magazine has ever published.

However, Groth and the Journal never printed a correction of the Englehart reference in the editorial.

But Groth apparently recognized the statement was erroneous at some point. In his 1994 anti-Shooter screed, “Jim Shooter, Our Nixon” (reprinted at tcj.com in 2011), he changed his tune somewhat on Englehart’s departure. The reader is still presented with an inaccurate view of the situation; Groth just didn't shoehorn Englehart into his attack to the same degree. Englehart is described in the essay as a creator “who also left under Shooter’s regime at Marvel” (TCJ #174, p. 18).

By itself, that reference may seem pretty benign. But it's a very slick bit of rhetorical spin. In the context of the essay, it’s very effective in falsely casting Englehart in the role of one of Shooter’s alleged victims.

First, note the falsehood of the word “regime.” An honest observer in command of the facts would say that Englehart left during Gerry Conway’s “regime,” not Shooter’s. Shooter was Marvel’s associate editor and Conway’s subordinate. But characterizing this period of Shooter’s employment as part of his “regime at Marvel” leads the reader to assume that Groth is speaking of Shooter’s tenure as editor-in-chief. This completely deflects attention from Conway and his exclusive role in Englehart's departure.

Second, note the presence of the word “also." This falsely identifies Englehart with the creators and staffers whom Groth describes at various points in the essay as “fired, driven off, fucked over, or otherwise insulted by Shooter”; whom Shooter “was routinely violating the professional dignity of” and “imprudently alienating”; whom “Marvel lost […] often because of an unresolvable dispute between the creator and Shooter”; and who “occasionally went on the record stating his unequivocal disdain for Shooter’s ethics and professionalism.” (TCJ #174, pp. 17 and 18)

What Groth is doing here is what I call “plausible deniability” writing. It’s a sleazy, manipulative rhetorical method that eschews direct statement in favor of juxtaposition and other forms of associative construction to make its points. In short, it implies its smears rather than states them. (Richard Nixon was fond of this deceitful rhetorical technique when it came to attacking his political opponents. Groth's "Our Nixon" title seems quite ironic.) One benefit of “plausible deniability” writing is the protection it would likely give Groth if, say, Shooter had sued him for libel over the essay. In this instance (and it's just one of the piece's numerous misrepresentations), Groth’s lawyer would probably just point out that Groth never directly said Englehart left Marvel because of Shooter’s allegedly shabby treatment. All he specifically wrote was that Englehart left Marvel “under Shooter’s regime.” Everything else was ambiguous at most. If readers wrongly inferred that Englehart left Marvel because of conflicts with Shooter, well, that’s the stupid readers’ fault, not Groth’s. He would probably say he is not responsible for erroneous interpretations of ambiguous statements or context. And that claim, in a court of law, is likely correct. He would likely prevail in a libel case because the individual statements technically aren’t false for the most part, and where they are false, they’re not specifically defamatory. Keep in mind that I'm not an attorney, but from what I know, this is what I'd expect.

Oh, and this probably goes without saying, but in the “Our Nixon” essay, Groth again made no mention of the fact that Englehart was working for Marvel at the time of Shooter’s termination, much less that he’d been regularly publishing new work through Marvel for the previous four years.

Note: Steve Englehart was sent a draft of the account that follows. He wrote back to say he had no corrections, and that he stands by what he has said over the years. Gerry Conway could not be reached.

With Shooter’s dealings with Englehart during his time as associate editor, two minor disputes are known.

The first was with the origin of The Shroud character that was published in Super-Villain Team-Up #7. Englehart deliberately appropriated the origin of Batman for the character. In Shooter’s testimony in the Marv Wolfman v. Marvel trial (click here), he recounted what came next:

As near as I can determine, Englehart has never publicly complained about the revisions to the story.

The second dispute occurred after Gerry Conway replaced Marv Wolfman as editor-in-chief. It related to the erroneous flagging of a story inconsistency in Super-Villain Team-Up #8. Judging from Conway and Englehart’s accounts, the dispute appears to have been far more with Conway than Shooter. But in Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, Sean Howe characterized it as a “blow-up” solely between Shooter and Englehart (p. 185). The incident is used as the principal support for a tendentious narrative that effectively blames Shooter for turning the editorial environment of Conway’s tenure, which lasted less than a month, “inescapably toxic.” Apparently towards that goal, Howe omits Conway from the dispute. The source or sources for Howe’s treatment are not included in the book’s endnotes, but it appears to be derived from Englehart’s interview in The Comics Journal #63 and Conway’s letter responding in TCJ #68.

Here’s what Englehart said happened:

Here’s what Conway had to say in his response:

Sean Howe, though, erroneously portrays the dispute as if it was only with Shooter. As can be seen, in Englehart’s statements, which were part of a larger attack on Conway, he says the specific dispute was with both Conway and Shooter, although it is not clear that he and Shooter ever spoke directly about it. Conway, in his response, describes the dispute as only between Englehart and himself. Shooter isn’t mentioned.

One also notes that Englehart deeply resented Conway due to this and other disputes during Conway's tenure. With Shooter, he held no grudge.

Howe apparently believes that if a conflict occurs in Jim Shooter's vicinity, it is automatically Jim Shooter's fault, and only Jim Shooter's fault. This is regardless of how the others involved see the situation. It is one example among many of Howe's nasty bias against Shooter, and the defamatory treatment of him in Howe's book.

As for Englehart’s departure from Marvel, he left after Conway took away a scripting assignment for The Avengers. Englehart said that Conway removed him from the series, and further claimed Conway said he wanted the assignment for himself (TCJ #63, p. 270). Conway said the removal was just for the story in that year’s The Avengers Annual, not the monthly series. The reason was because of Englehart’s missed deadlines, and not because he wanted to take over as the series’ scriptwriter. (TCJ 68, p. 23). Jim Shooter, in a 2011 blog comment (click here), more or less confirmed Conway’s account.

As for Englehart's career afterward, he immediately moved over to DC, where his most notable effort was a Batman run in Detective Comics with artist Marshall Rogers. He worked at DC on various titles before quitting over a payment dispute in late 1978 or early 1979. He left the field for three years, reemerging in 1982 with his author-owned feature Coyote. It was originally published by Eclipse, and Englehart took it to Marvel’s Epic imprint a few months later. He resumed working on company-owned titles for both Marvel and DC in 1985. He stayed at DC through 1987, and was removed from his Marvel assignments in 1989 after conflicts with Tom DeFalco, Jim Shooter’s successor as editor-in-chief. In 1992, he worked on the X-O Manowar and Shadowman titles under Shooter at Valiant, but left after a few months due to differences with Shooter about editorial direction. Englehart says the parting was amicable (click here). Shooter says otherwise (click here), although he still holds Englehart’s ability in high regard (click here). Englehart spent the next several years doing scriptwriting work for various publishers, including Marvel and DC. He left the comics field for good in 2006.

Related posts:

-- Tony Isabella

-- Gerry Conway

-- Mary Skrenes

-- Len Wein

For the introduction to "The Jim Shooter 'Victim' Files" series, click here.

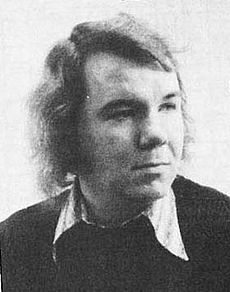

Jim Shooter and Steve Englehart, at the 1982 San Diego Comicon

Born in 1947, Steve Englehart broke into the comics business in late 1970. He graduated with a bachelor's degree in psychology from Wesleyan University in 1969. He also served for a time in the U. S. Army. He started as a freelance artist for various publishers, but quickly shifted to scriptwriting. Long runs on Marvel’s Captain America and The Avengers made him one of the field's most admired scriptwriters before he left for DC in 1976.

Before getting into the specific circumstances of Englehart’s departure from Marvel, I would like to discuss at length how Englehart’s situation has been exploited to attack Jim Shooter. It’s a good study in the tactics Gary Groth and Sean Howe, Shooter’s most conspicuous detractors, have used in efforts to defame him.

Given the prominent role Groth and The Comics Journal have in shaping perceptions of comics history, his portrayal of Shooter's dealings with various comics personnel will be discussed in each instance. For the same reason, Sean Howe's treatments in Marvel Comics: The Untold Story will be examined as well.

In Groth’s 1987 editorial about Jim Shooter’s termination as Marvel editor-in-chief, he included Englehart in a list of “the vast number of creators fired or otherwise driven to leave Marvel by Shooter” (TCJ #117, p. 6). This reference should have struck a discordant note with any knowledgeable reader.

The most immediate reason was that, at the time of Shooter’s firing in April 1987, Englehart was working for Marvel. He was the regular scriptwriter on three ongoing company-owned titles: Fantastic Four, Silver Surfer, and West Coast Avengers. He had been writing at least two titles a month for the company’s various imprints for the previous two years. He began regularly publishing new work through Marvel again in February of 1983, when the first issue of his creator-owned series Coyote shipped to retailers.

Beyond that, it was well known in comics circles that Englehart quit Marvel in 1976 because of conflicts with Gerry Conway, who was then the company’s editor-in-chief. One reason it was known was an interview with Englehart in The Comics Journal #63 that Groth helped conduct. Englehart discussed his problems with Conway at length. His statements gained additional notoriety when Conway responded with a letter, published in The Comics Journal #68, that may well be the single most intemperate, vituperative, and outright nasty piece of writing the magazine has ever published.

However, Groth and the Journal never printed a correction of the Englehart reference in the editorial.

But Groth apparently recognized the statement was erroneous at some point. In his 1994 anti-Shooter screed, “Jim Shooter, Our Nixon” (reprinted at tcj.com in 2011), he changed his tune somewhat on Englehart’s departure. The reader is still presented with an inaccurate view of the situation; Groth just didn't shoehorn Englehart into his attack to the same degree. Englehart is described in the essay as a creator “who also left under Shooter’s regime at Marvel” (TCJ #174, p. 18).

By itself, that reference may seem pretty benign. But it's a very slick bit of rhetorical spin. In the context of the essay, it’s very effective in falsely casting Englehart in the role of one of Shooter’s alleged victims.

First, note the falsehood of the word “regime.” An honest observer in command of the facts would say that Englehart left during Gerry Conway’s “regime,” not Shooter’s. Shooter was Marvel’s associate editor and Conway’s subordinate. But characterizing this period of Shooter’s employment as part of his “regime at Marvel” leads the reader to assume that Groth is speaking of Shooter’s tenure as editor-in-chief. This completely deflects attention from Conway and his exclusive role in Englehart's departure.

Second, note the presence of the word “also." This falsely identifies Englehart with the creators and staffers whom Groth describes at various points in the essay as “fired, driven off, fucked over, or otherwise insulted by Shooter”; whom Shooter “was routinely violating the professional dignity of” and “imprudently alienating”; whom “Marvel lost […] often because of an unresolvable dispute between the creator and Shooter”; and who “occasionally went on the record stating his unequivocal disdain for Shooter’s ethics and professionalism.” (TCJ #174, pp. 17 and 18)

What Groth is doing here is what I call “plausible deniability” writing. It’s a sleazy, manipulative rhetorical method that eschews direct statement in favor of juxtaposition and other forms of associative construction to make its points. In short, it implies its smears rather than states them. (Richard Nixon was fond of this deceitful rhetorical technique when it came to attacking his political opponents. Groth's "Our Nixon" title seems quite ironic.) One benefit of “plausible deniability” writing is the protection it would likely give Groth if, say, Shooter had sued him for libel over the essay. In this instance (and it's just one of the piece's numerous misrepresentations), Groth’s lawyer would probably just point out that Groth never directly said Englehart left Marvel because of Shooter’s allegedly shabby treatment. All he specifically wrote was that Englehart left Marvel “under Shooter’s regime.” Everything else was ambiguous at most. If readers wrongly inferred that Englehart left Marvel because of conflicts with Shooter, well, that’s the stupid readers’ fault, not Groth’s. He would probably say he is not responsible for erroneous interpretations of ambiguous statements or context. And that claim, in a court of law, is likely correct. He would likely prevail in a libel case because the individual statements technically aren’t false for the most part, and where they are false, they’re not specifically defamatory. Keep in mind that I'm not an attorney, but from what I know, this is what I'd expect.

Oh, and this probably goes without saying, but in the “Our Nixon” essay, Groth again made no mention of the fact that Englehart was working for Marvel at the time of Shooter’s termination, much less that he’d been regularly publishing new work through Marvel for the previous four years.

Note: Steve Englehart was sent a draft of the account that follows. He wrote back to say he had no corrections, and that he stands by what he has said over the years. Gerry Conway could not be reached.

With Shooter’s dealings with Englehart during his time as associate editor, two minor disputes are known.

The first was with the origin of The Shroud character that was published in Super-Villain Team-Up #7. Englehart deliberately appropriated the origin of Batman for the character. In Shooter’s testimony in the Marv Wolfman v. Marvel trial (click here), he recounted what came next:

It was plagiarism. And I thought that was a very bad idea. Steve Englehart was a very important writer. So I called him, and I said, "Steve, you seem to be doing the origin of Batman here." And he said, "Yes, I am." And I said, "You can't do that." And he said, "Yes, I can." That conversation was getting nowhere. I thought, let me talk to Marv about this. I went to Marv and I showed it to him. And he asked me to change it as little as possible because we wanted to not offend Steve any more than absolutely necessary but to make it so it wasn't plagiarism. So I did the best I could to alter it to, you know, to meet that standard.

As near as I can determine, Englehart has never publicly complained about the revisions to the story.

The origin of Batman.. or The Shroud? From Super-Villain Team-Up #7. Script by Steve Englehart (with unspecified revisions by Jim Shooter). Penciled by Herb Trimpe and inked by Pablo Marcos.

The second dispute occurred after Gerry Conway replaced Marv Wolfman as editor-in-chief. It related to the erroneous flagging of a story inconsistency in Super-Villain Team-Up #8. Judging from Conway and Englehart’s accounts, the dispute appears to have been far more with Conway than Shooter. But in Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, Sean Howe characterized it as a “blow-up” solely between Shooter and Englehart (p. 185). The incident is used as the principal support for a tendentious narrative that effectively blames Shooter for turning the editorial environment of Conway’s tenure, which lasted less than a month, “inescapably toxic.” Apparently towards that goal, Howe omits Conway from the dispute. The source or sources for Howe’s treatment are not included in the book’s endnotes, but it appears to be derived from Englehart’s interview in The Comics Journal #63 and Conway’s letter responding in TCJ #68.

Here’s what Englehart said happened:

In the same three-week period, when Conway was the editor, [...] a lot of people went out at that time. It had gotten to the point where a lot of people just didn't feel it was what they had signed on for. [...] It was a strange three weeks [...] the first week Conway and Shooter--his Assistant Editor, or the right-hand man--called me up and said, “We really don’t like the Super-Villain Team-Up you just wrote because you said the Sub-Mariner’s father did or didn’t do something.” It’s on page two of issue six or seven or something. I don’t even know what it is now. But they said, “You did this.” I said, “No, I really didn’t.” And they said, “We know you did, because we were told by whoever proofread that you did it.” I said, “I’ve got the script right here, and I didn’t say that.” And it was like, “Yes, you did, and you’re gonna pay for it. You’re really in trouble for doing this kind of stuff.” So I took my Xerox copy of the script and I Xeroxed off the page and I sent it to them.

The second week I got a call from Conway saying, “We’re really sorry. We were misinformed. I see your script, you’re right. I went back and looked at it, everything you said was true, hey look, no hard feelings, huh, I’m just getting started and I don’t really know how to do all this shit and let’s just let bygones be bygones.” (TCJ #63, p. 270)

Here’s what Conway had to say in his response:

When I became editor[-in-chief] at Marvel, I expected some problems with, among other people, Steve Englehart [...] Steve was well-known at Marvel as a balloon-headed egotist with a short fuse. [...] He states rightly, that I called him up concerned about an error in his script--not a minor error as he asserts, but a major continuity error. He told me it wasn’t his doing; on the information I had, I thought he was lying. (This may come as a shock to those of you fresh from the egg, but yes, Steve has been known to bend the truth just a tad now and then.) He did indeed send me a Xerox of his script, though of course this proved nothing since scripts can be retyped; but I checked it out, found out I was wrong, and as Steve tells you in his interview--I called him and apologized, admitting my mistake. (TCJ #68, pp. 23-25)

Sean Howe, though, erroneously portrays the dispute as if it was only with Shooter. As can be seen, in Englehart’s statements, which were part of a larger attack on Conway, he says the specific dispute was with both Conway and Shooter, although it is not clear that he and Shooter ever spoke directly about it. Conway, in his response, describes the dispute as only between Englehart and himself. Shooter isn’t mentioned.

One also notes that Englehart deeply resented Conway due to this and other disputes during Conway's tenure. With Shooter, he held no grudge.

Howe apparently believes that if a conflict occurs in Jim Shooter's vicinity, it is automatically Jim Shooter's fault, and only Jim Shooter's fault. This is regardless of how the others involved see the situation. It is one example among many of Howe's nasty bias against Shooter, and the defamatory treatment of him in Howe's book.

As for Englehart’s departure from Marvel, he left after Conway took away a scripting assignment for The Avengers. Englehart said that Conway removed him from the series, and further claimed Conway said he wanted the assignment for himself (TCJ #63, p. 270). Conway said the removal was just for the story in that year’s The Avengers Annual, not the monthly series. The reason was because of Englehart’s missed deadlines, and not because he wanted to take over as the series’ scriptwriter. (TCJ 68, p. 23). Jim Shooter, in a 2011 blog comment (click here), more or less confirmed Conway’s account.